❍ In order of appearance in the scenario

❍ 2022

Commissioner

Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles

Organisation

Direction des Arts plastiques contemporains

Coordination

Pascale Viscardy

Institutional partner

Wallonie Bruxelles-International

Coordination

Pascale Eben, France Dosogne

❍ Winter

Collective

Sophie Boiron, Valentin Bollaert, Simona Denicolai, Pauline Fockedey, Pierre Huyghebaert, Antoinette Jattiot, Ivo Provoost

❍ 2023

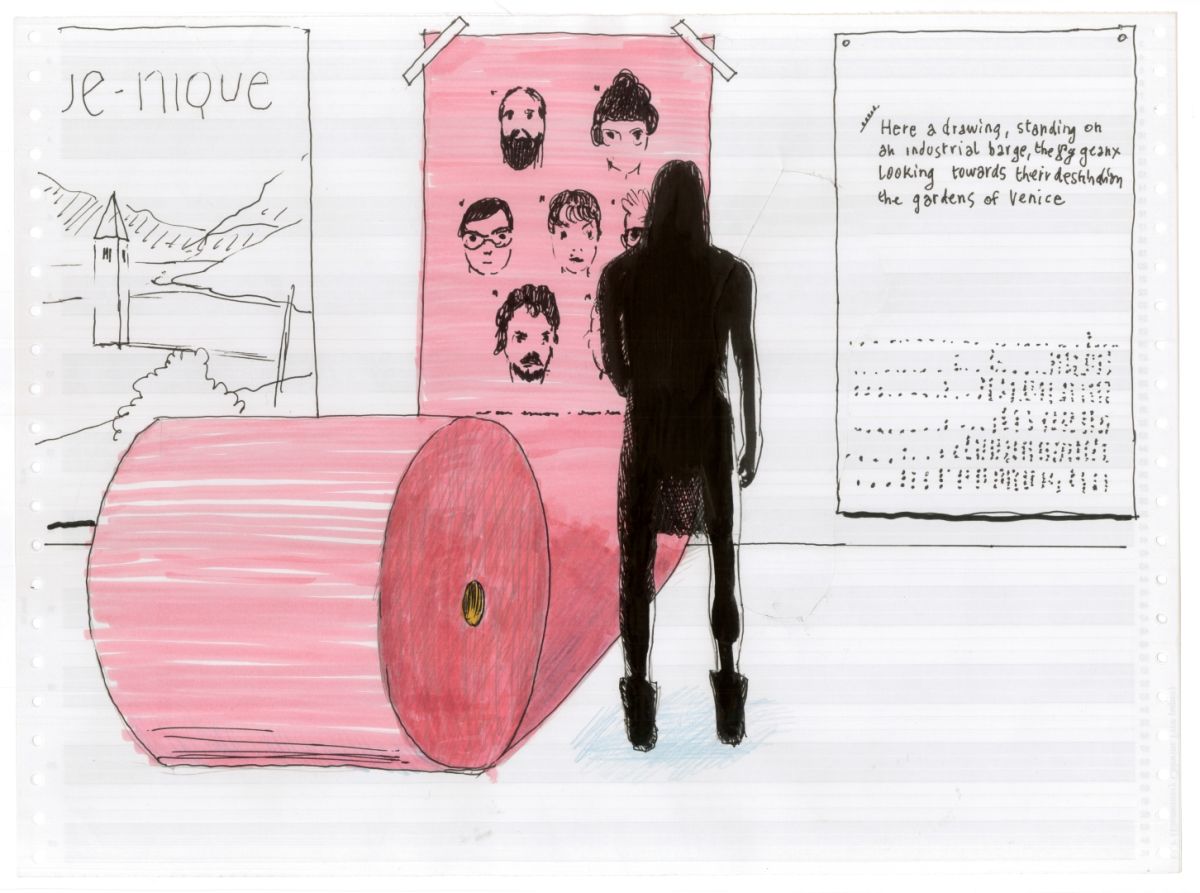

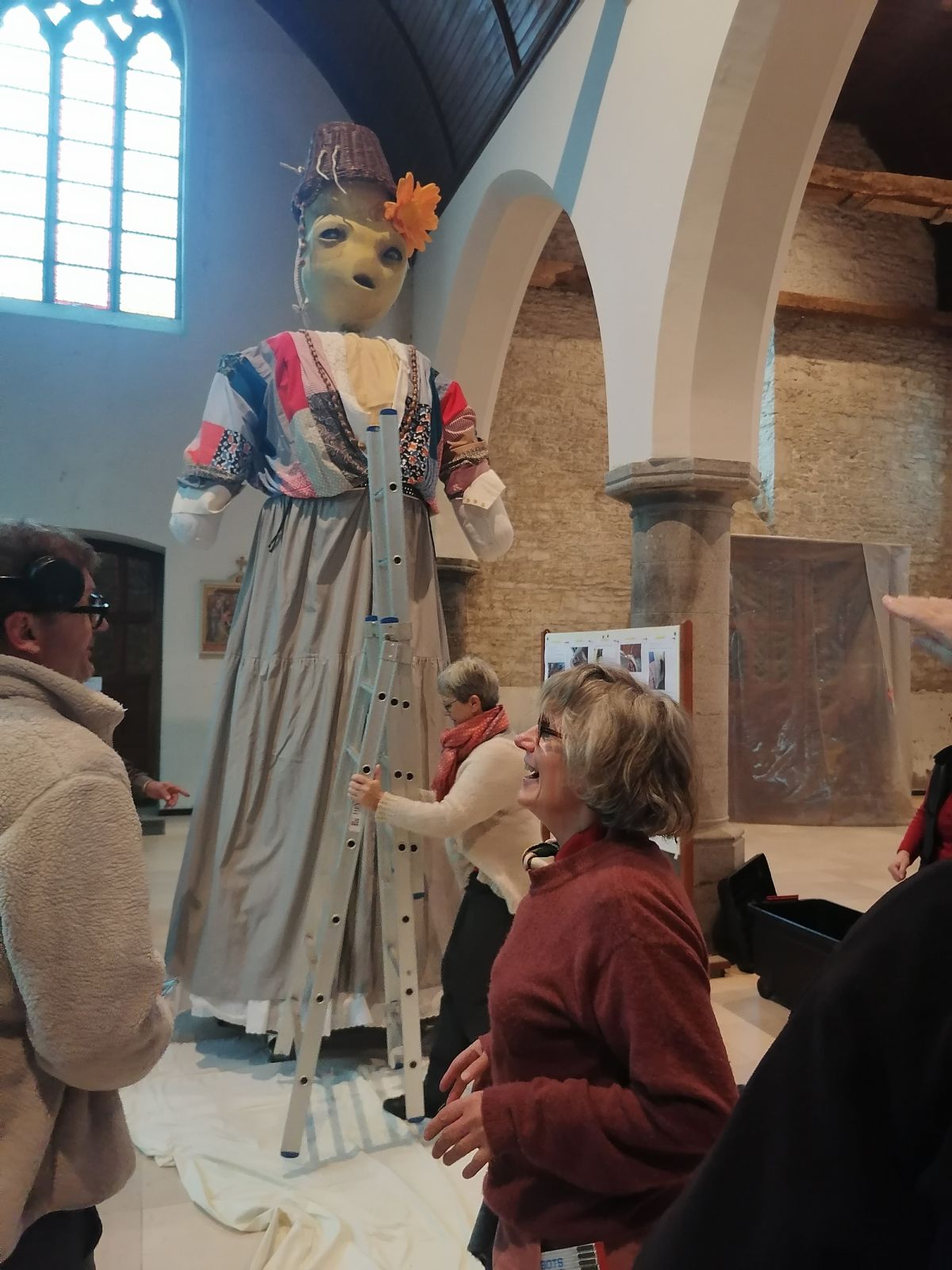

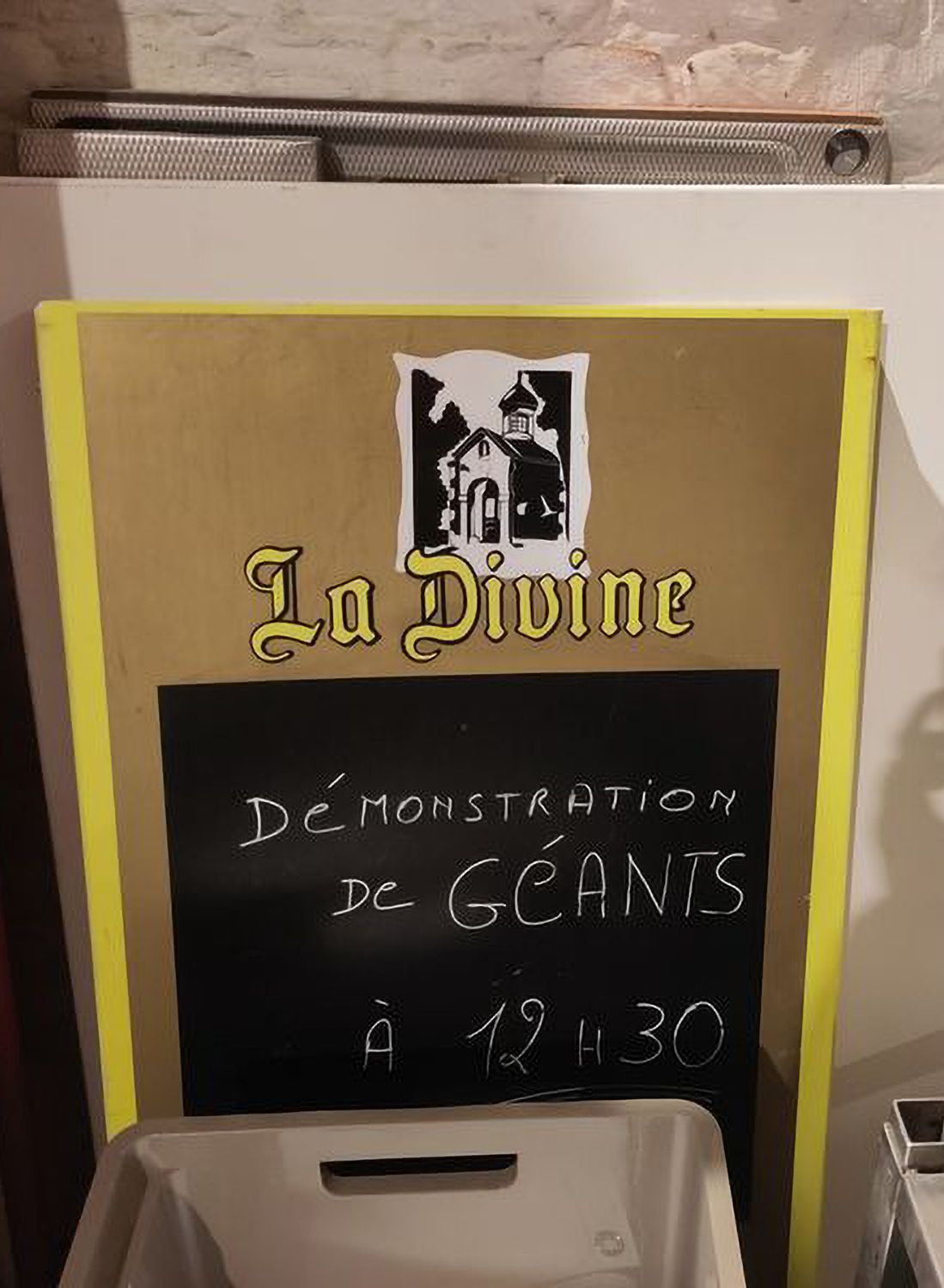

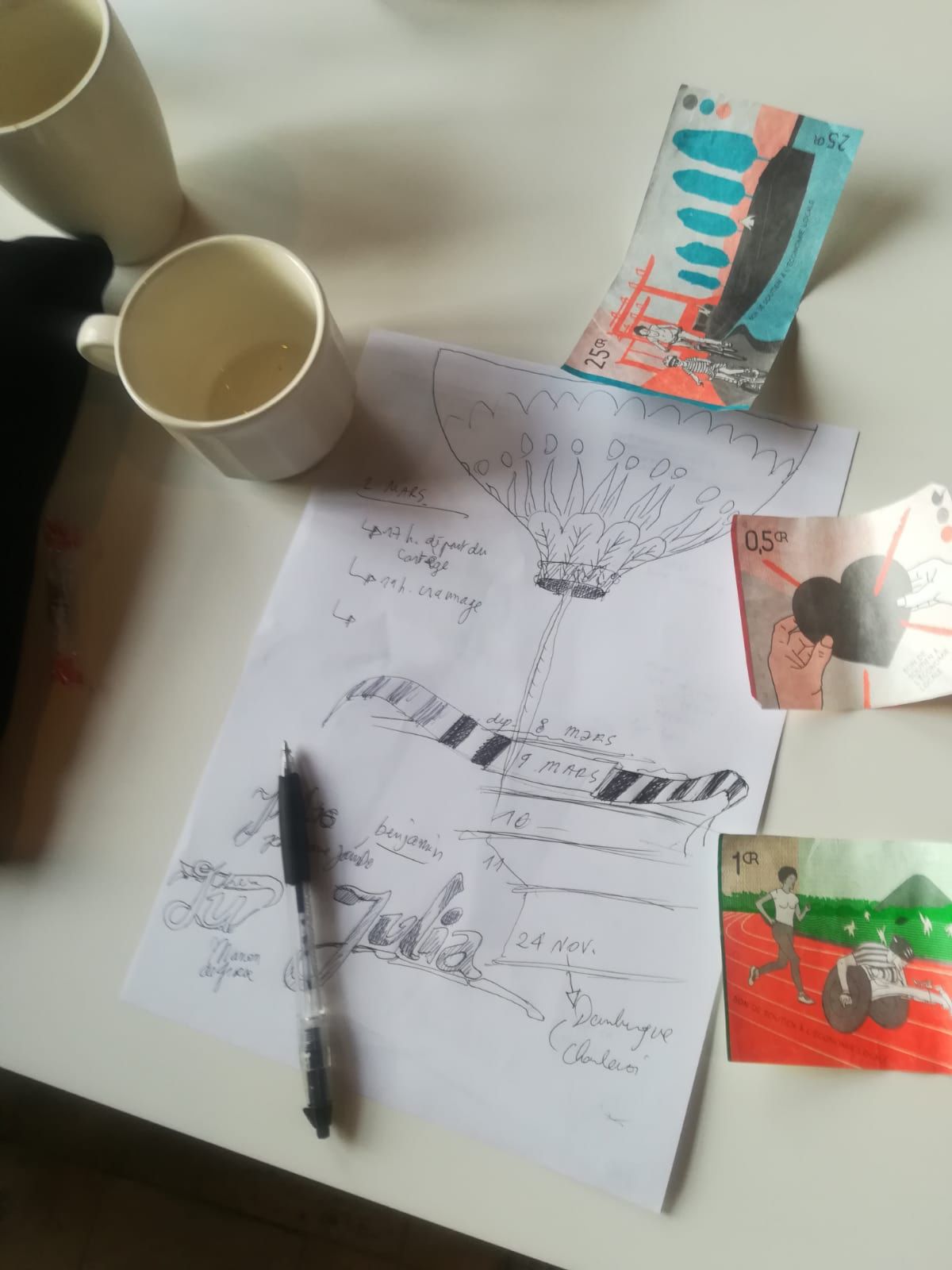

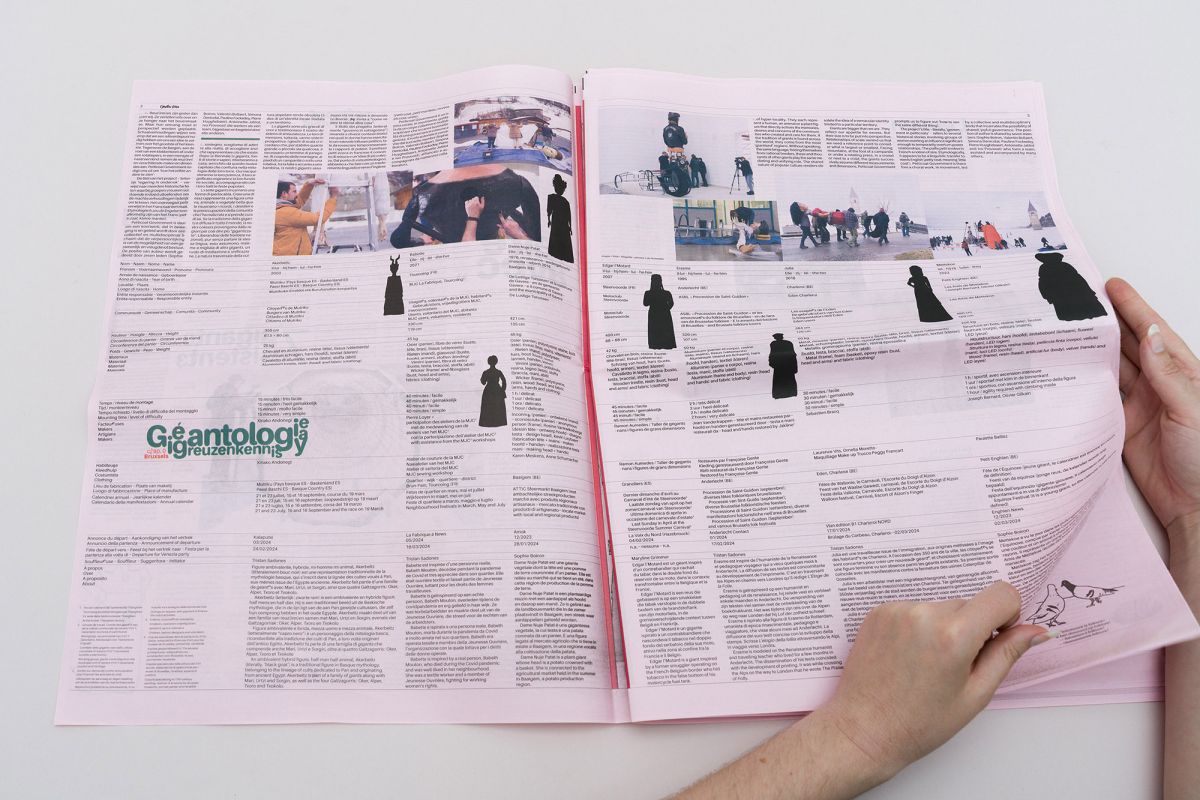

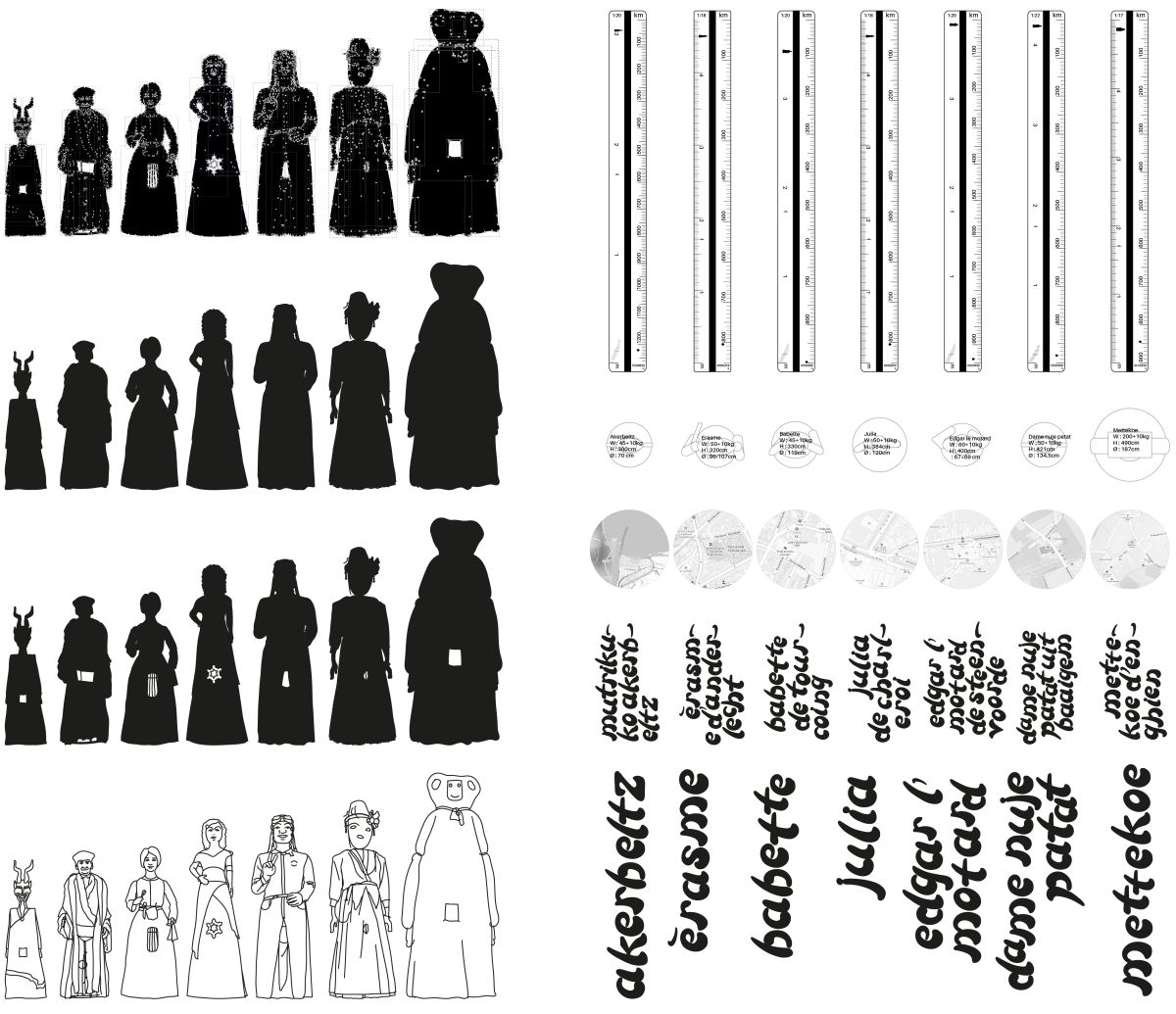

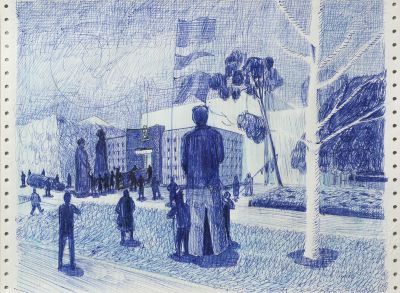

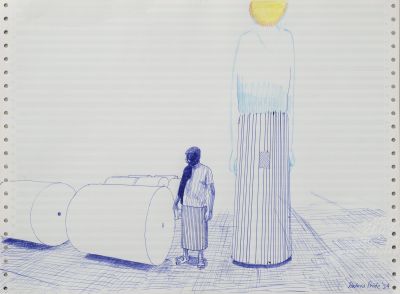

Geantology

Tristan Sadones

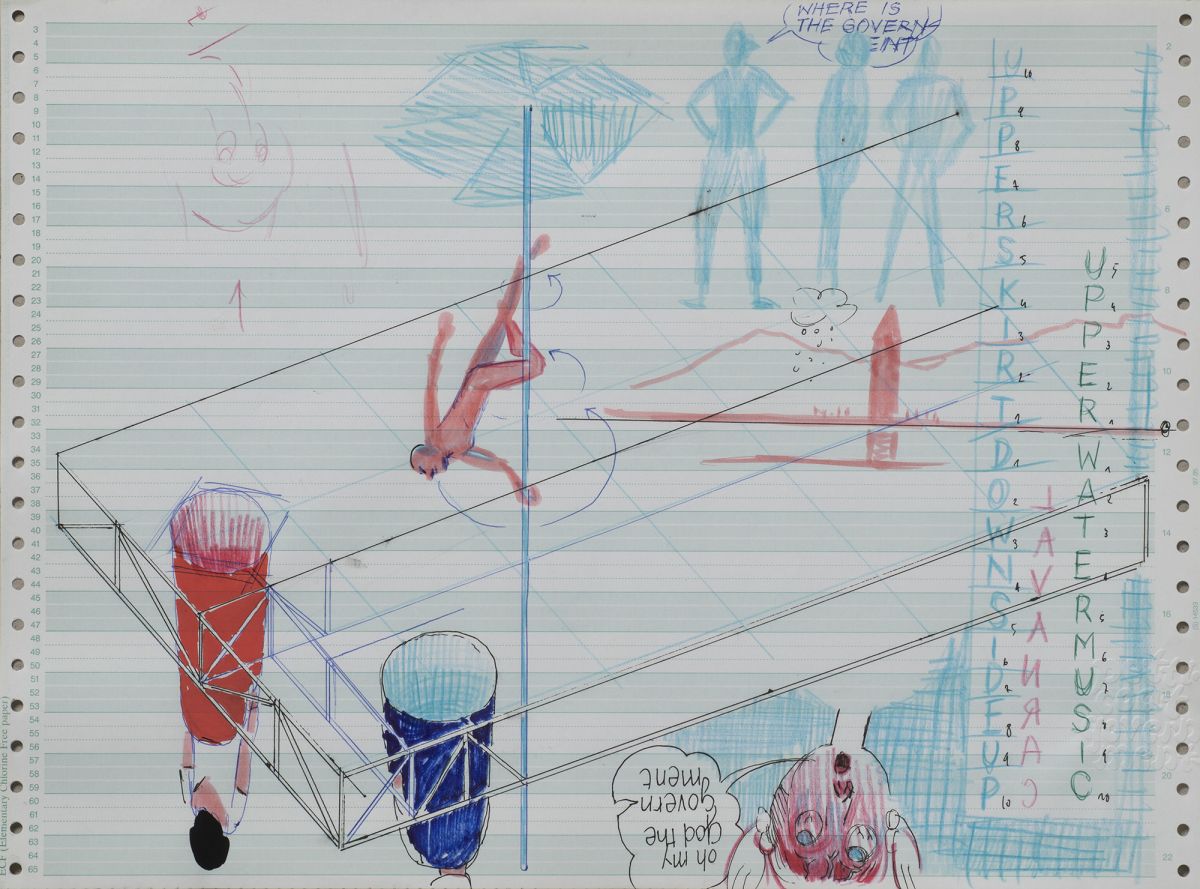

Dancing boy

Hugo Mertens

Typography

Groupe de Recherche Crickx, OSP, MiratMasson, Bye Bye Binary

Expertise

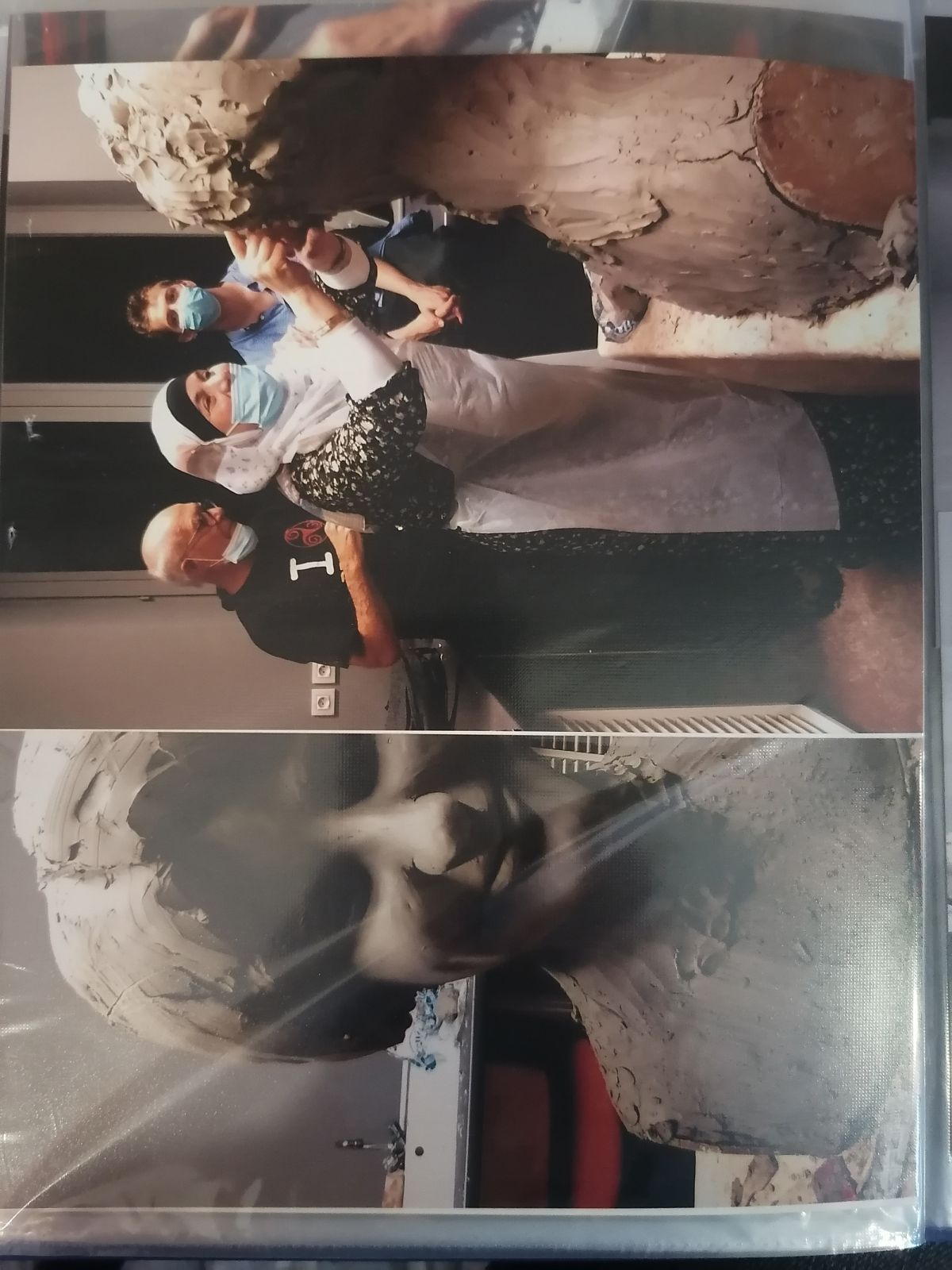

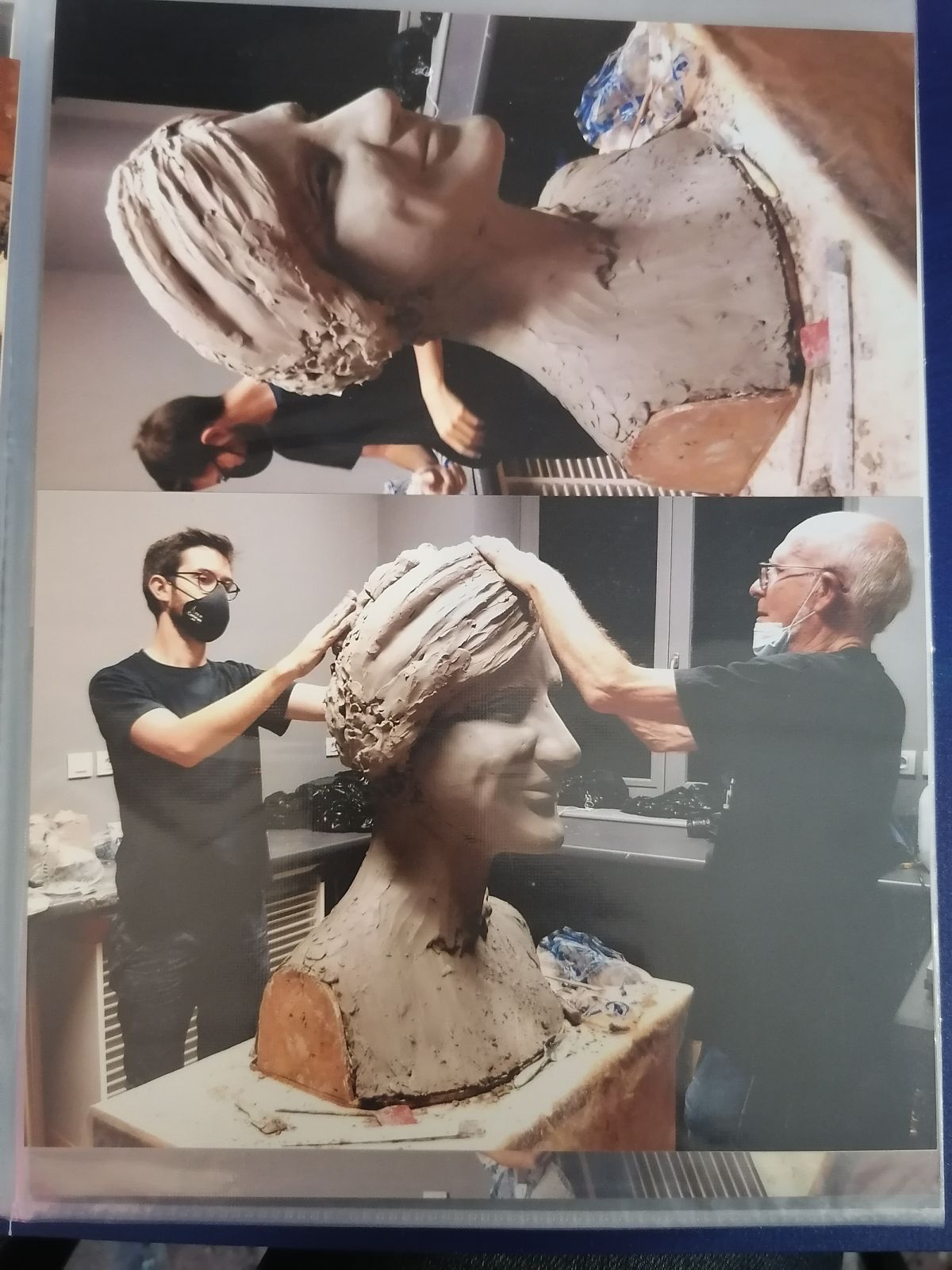

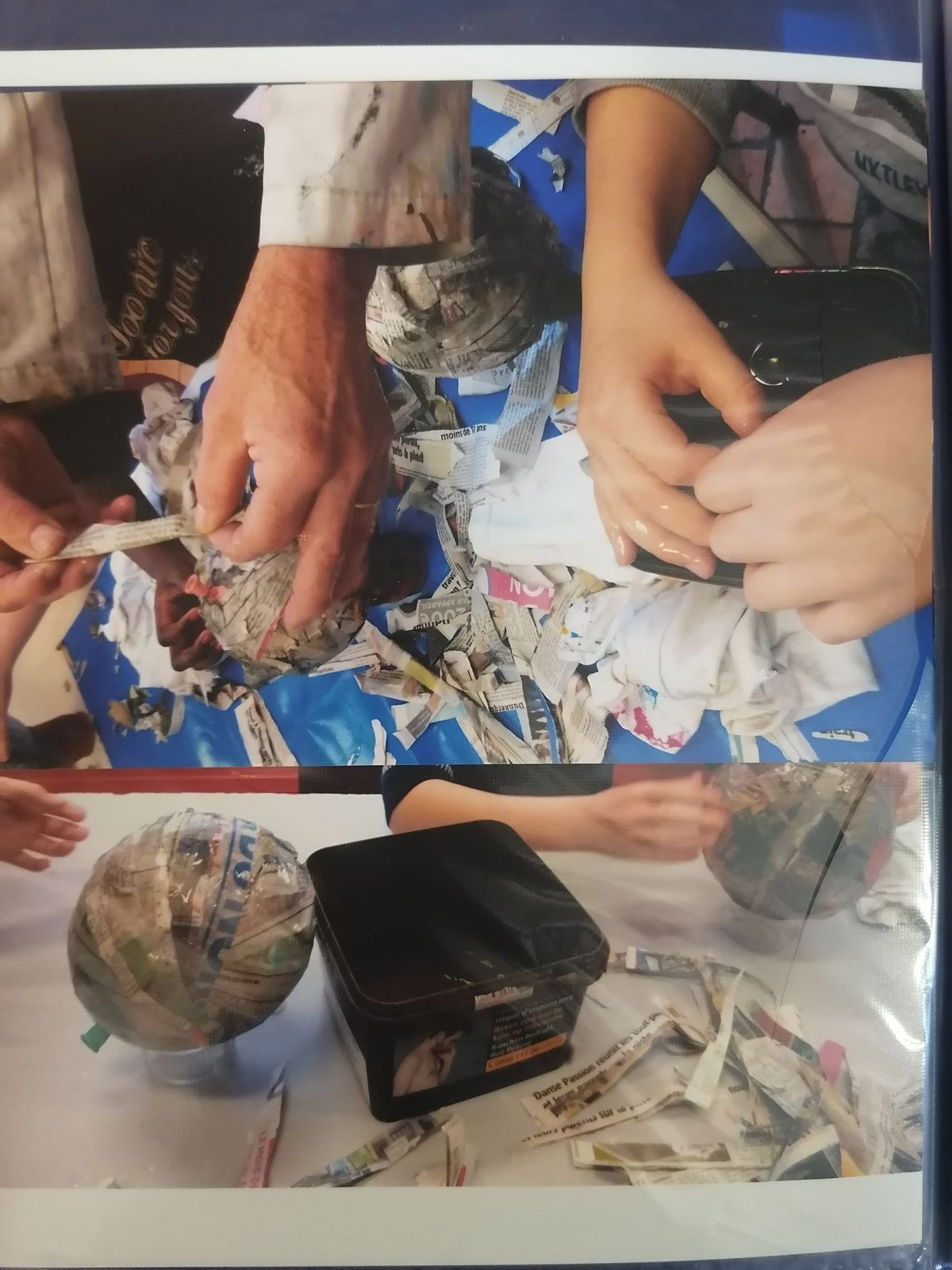

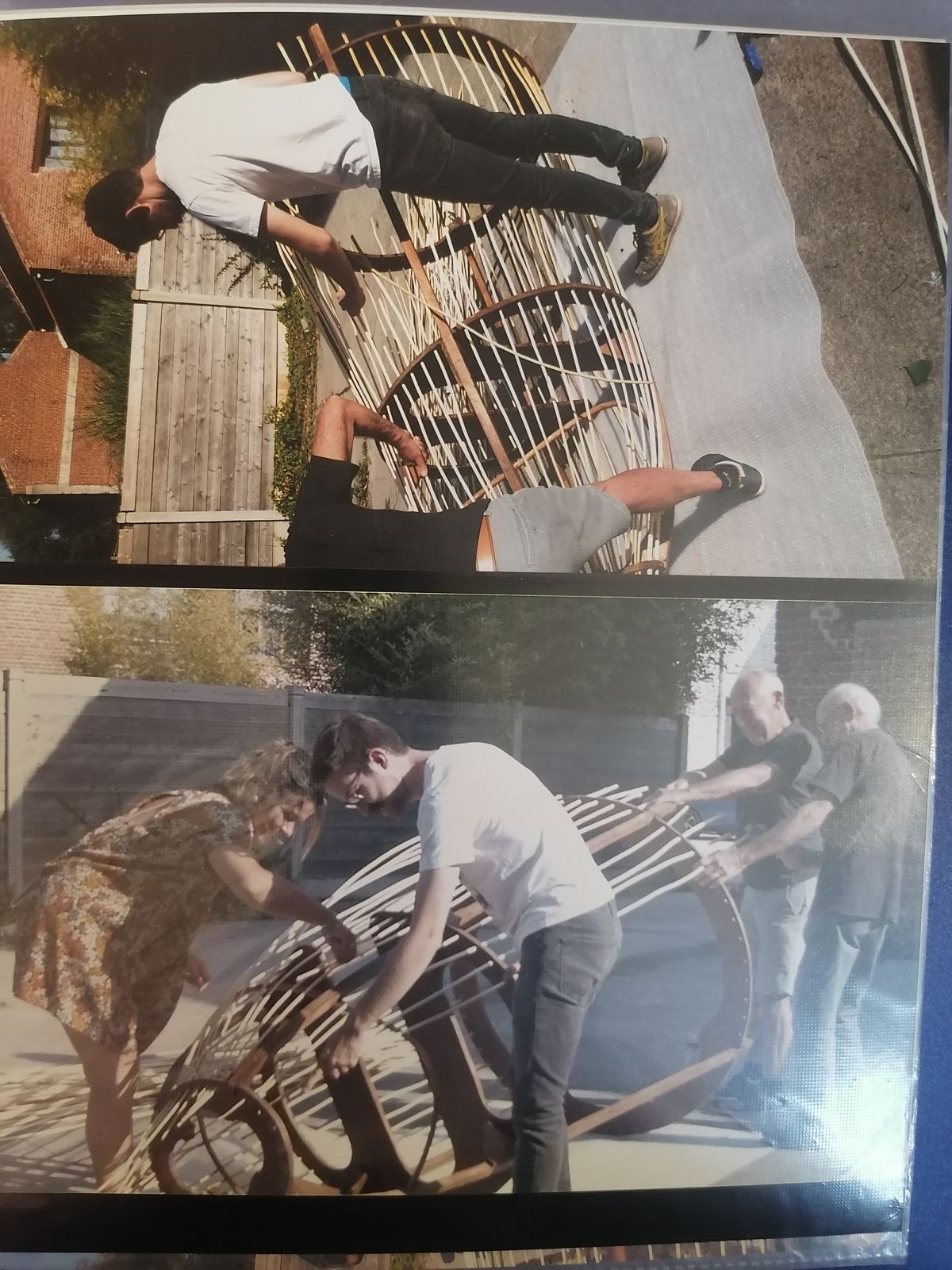

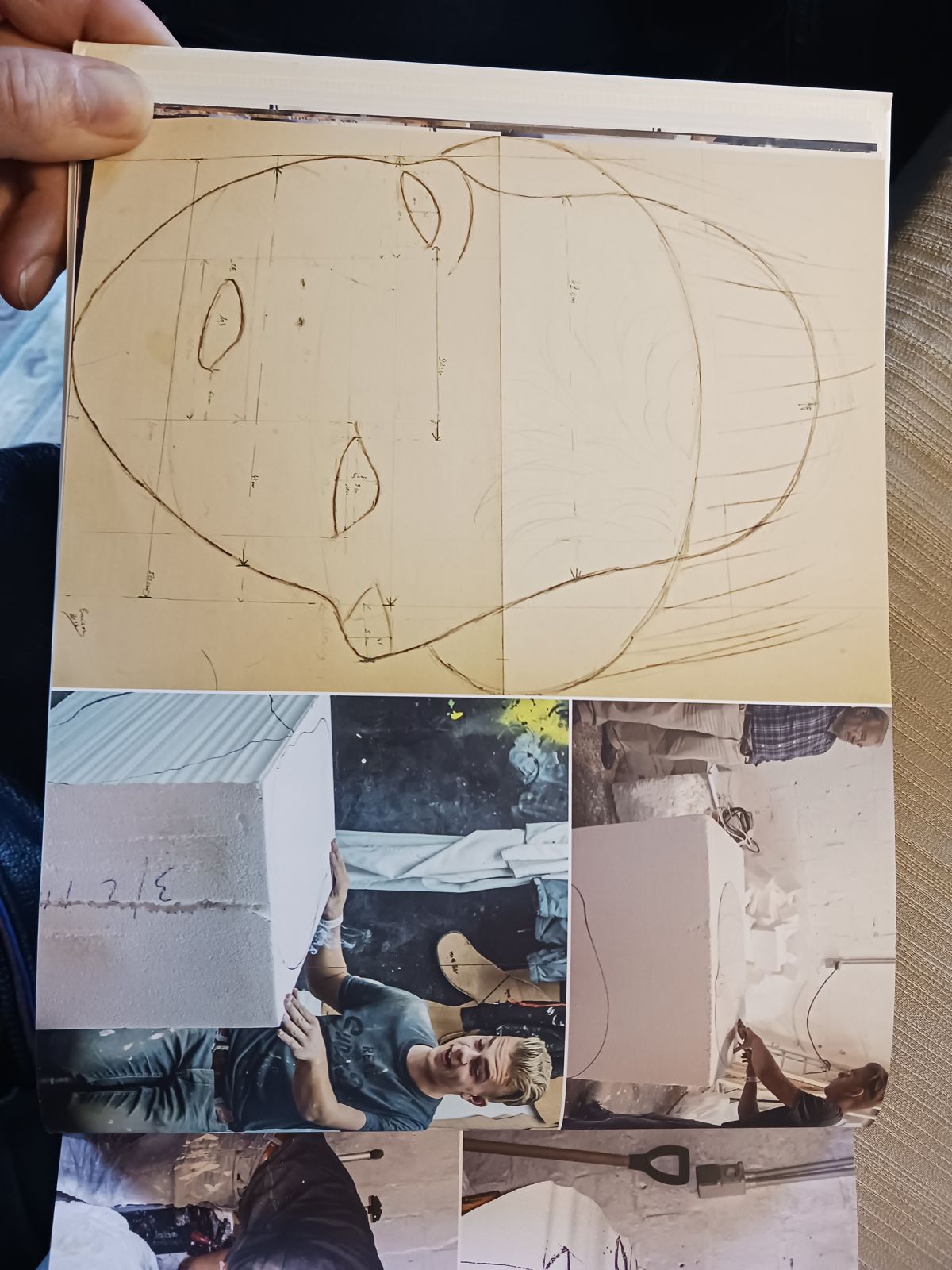

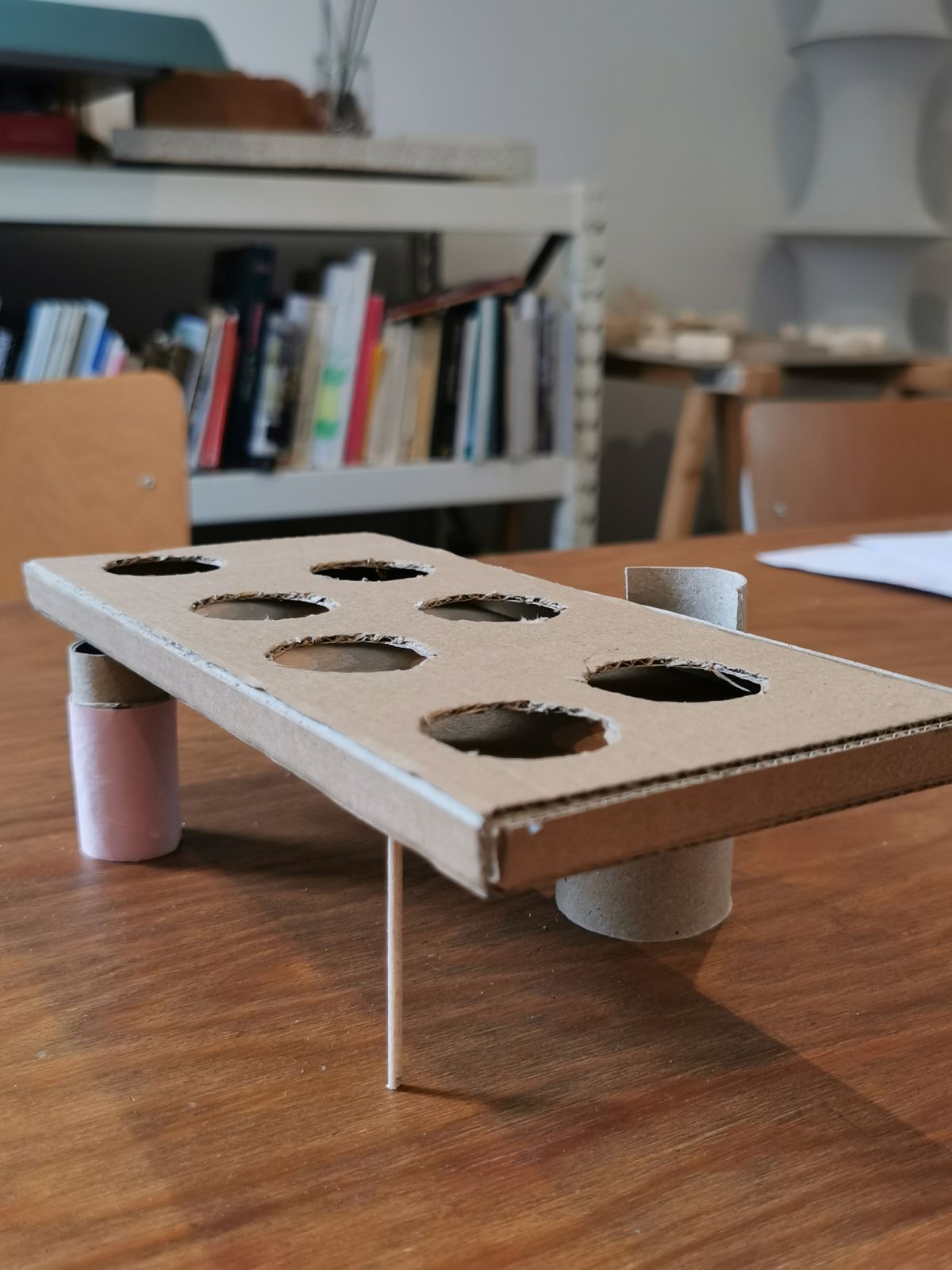

Atelier des Géants (Dorian Demarcq)

Catalogue publishers

MOREpublishers (Amélie Laplanche, Tim Ryckaert)

Partner institutions

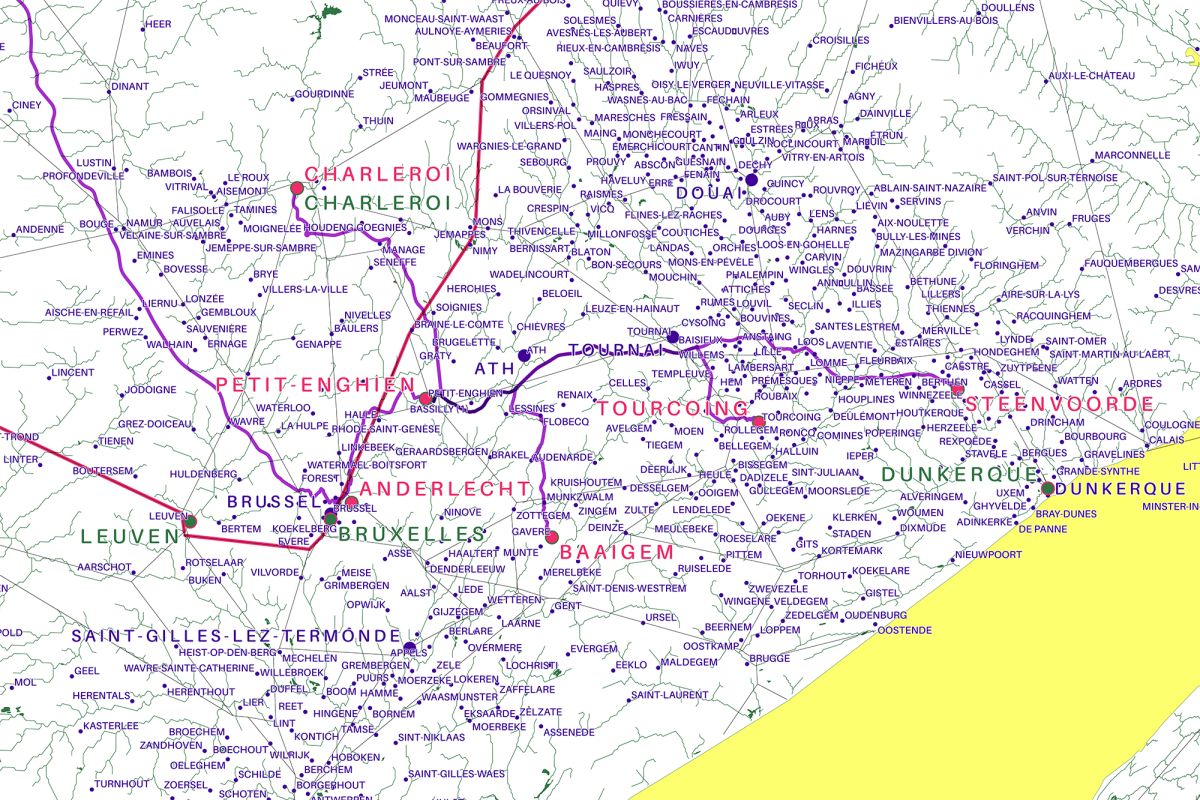

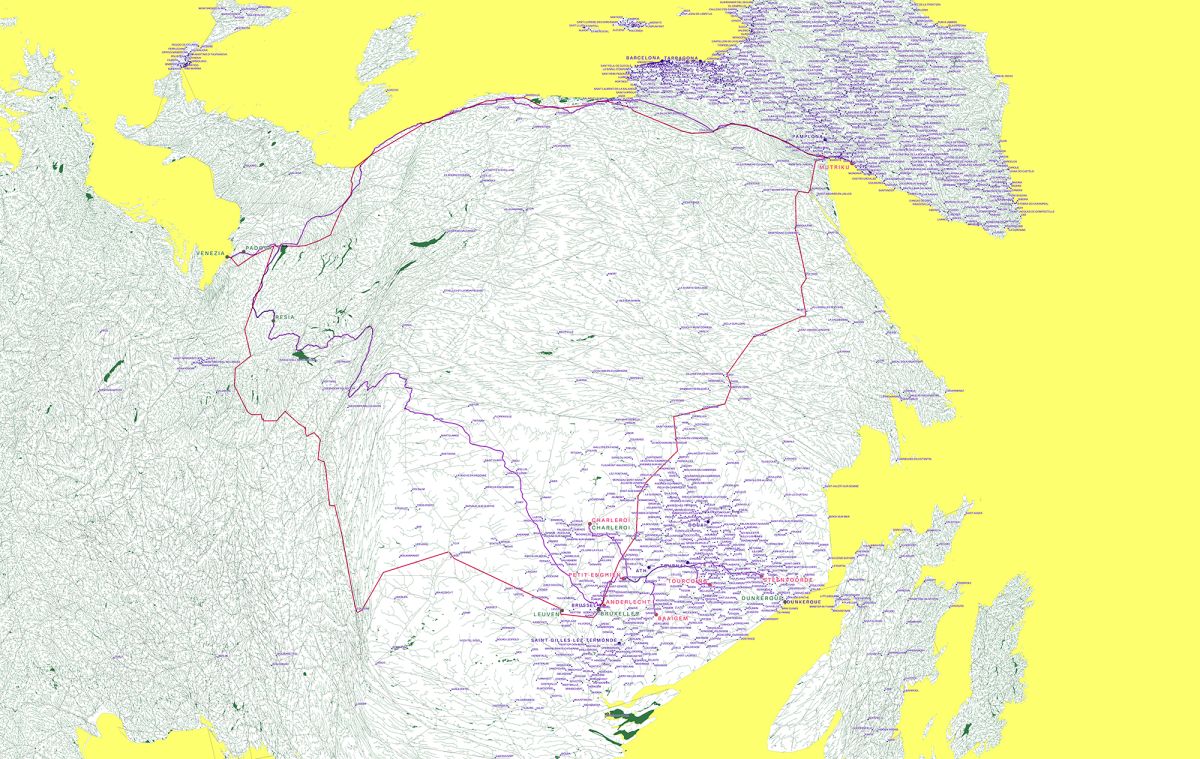

◡ BPS22, Charleroi

Direction

Pierre-Olivier Rollin

◡ FRAC Dunkerque

Direction

Keren Detton

❍ Spring

Gallery

LMNO

Direction

Natacha et Olivier Legrain-Mottart

Collaboration

Julie Gaillard

Accounting

C-ZAM (Gaëlle Meeus)

❍ Summer

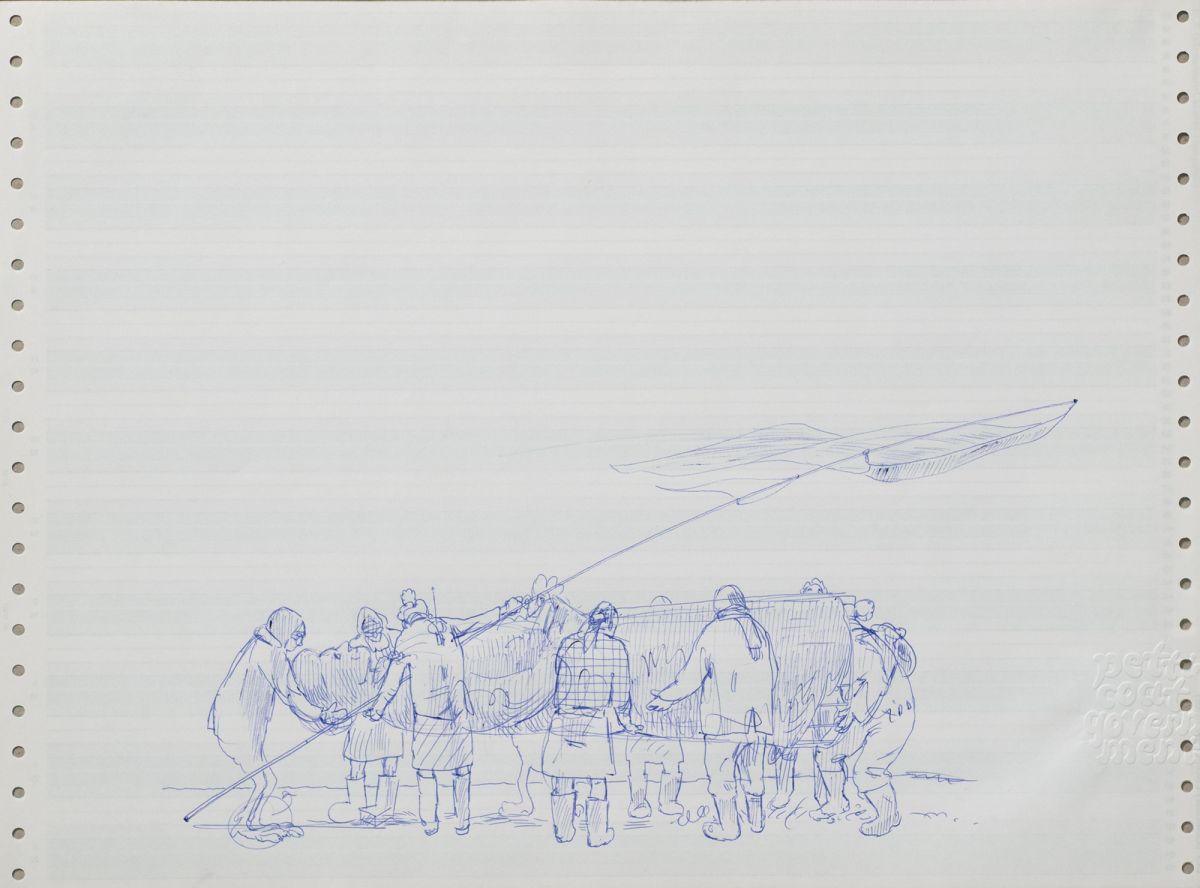

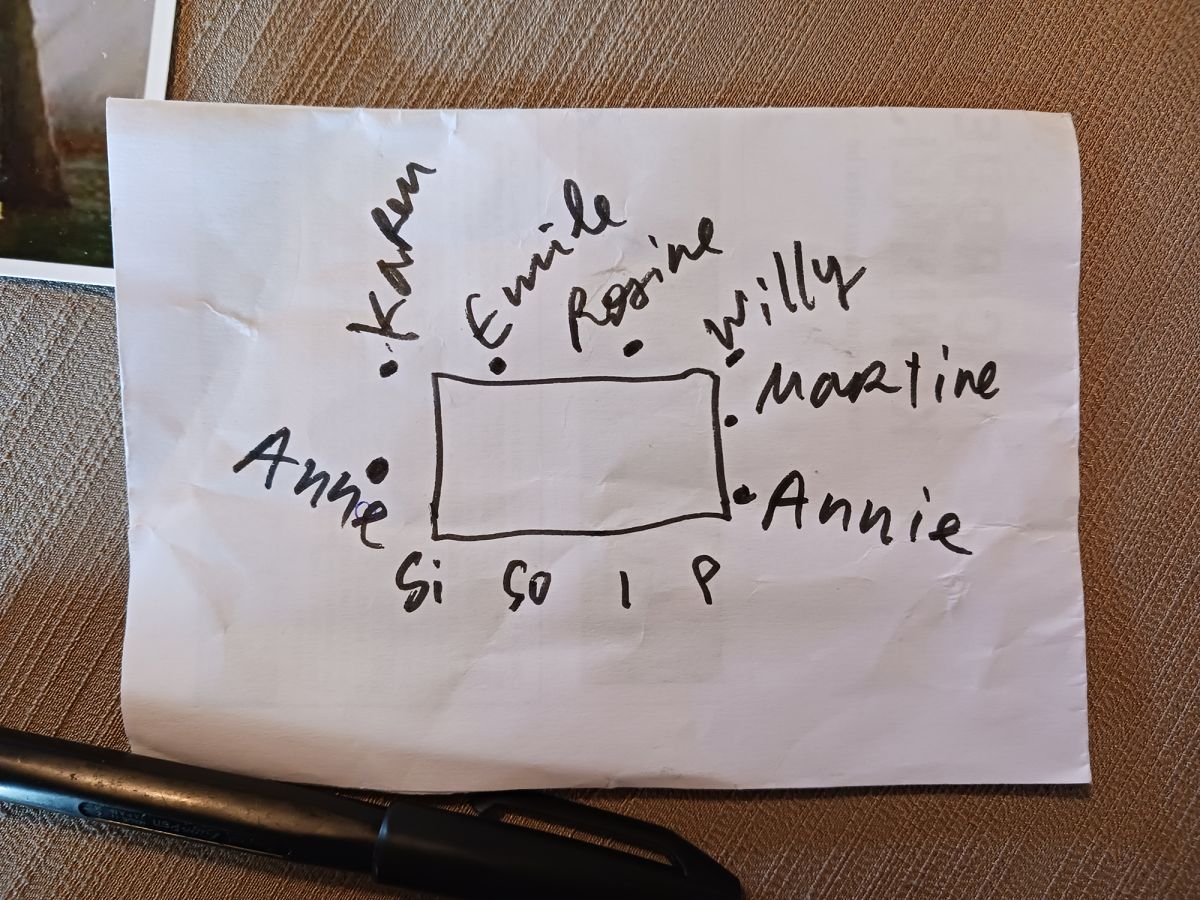

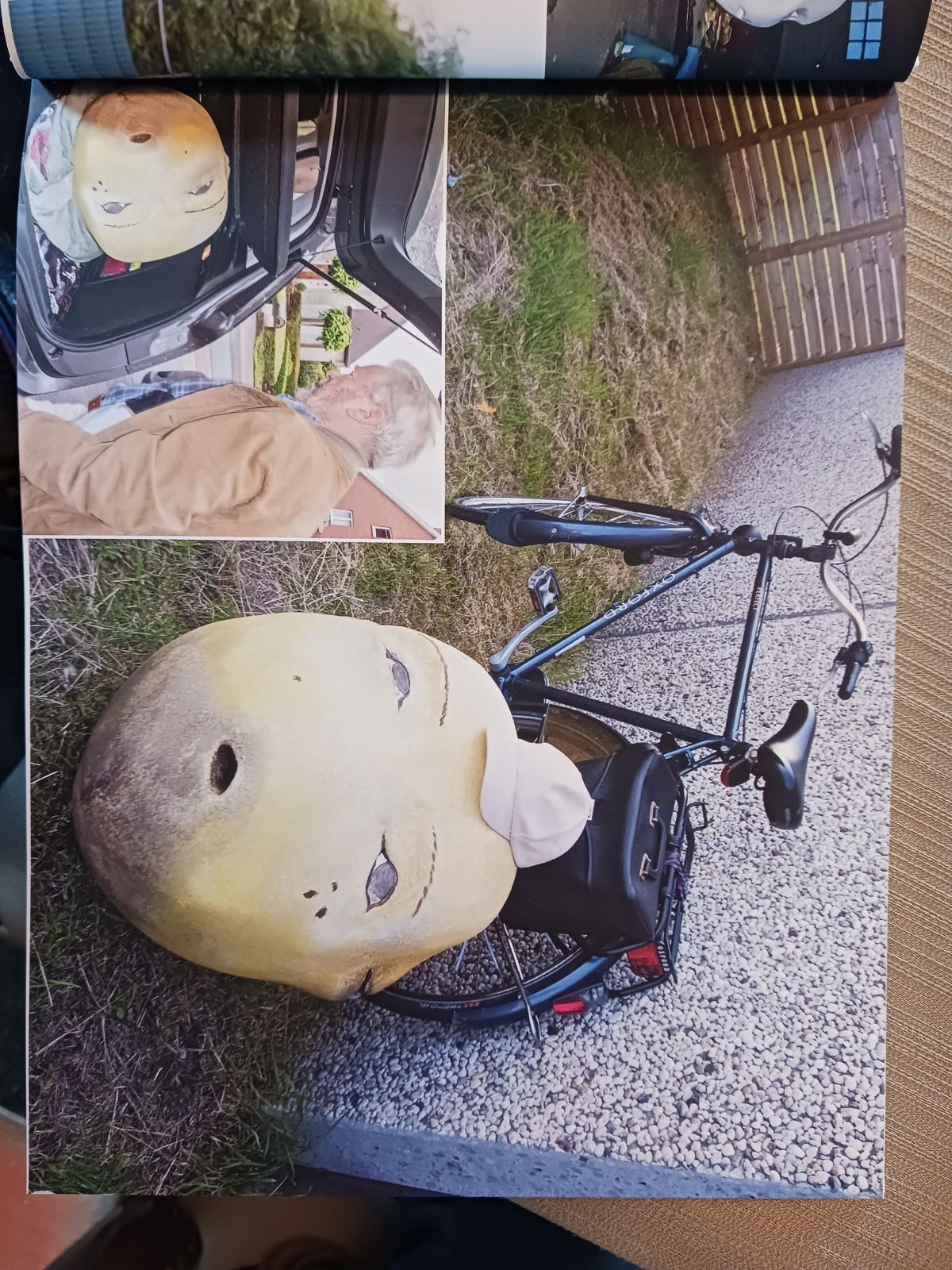

Communities around the giants (travellers)

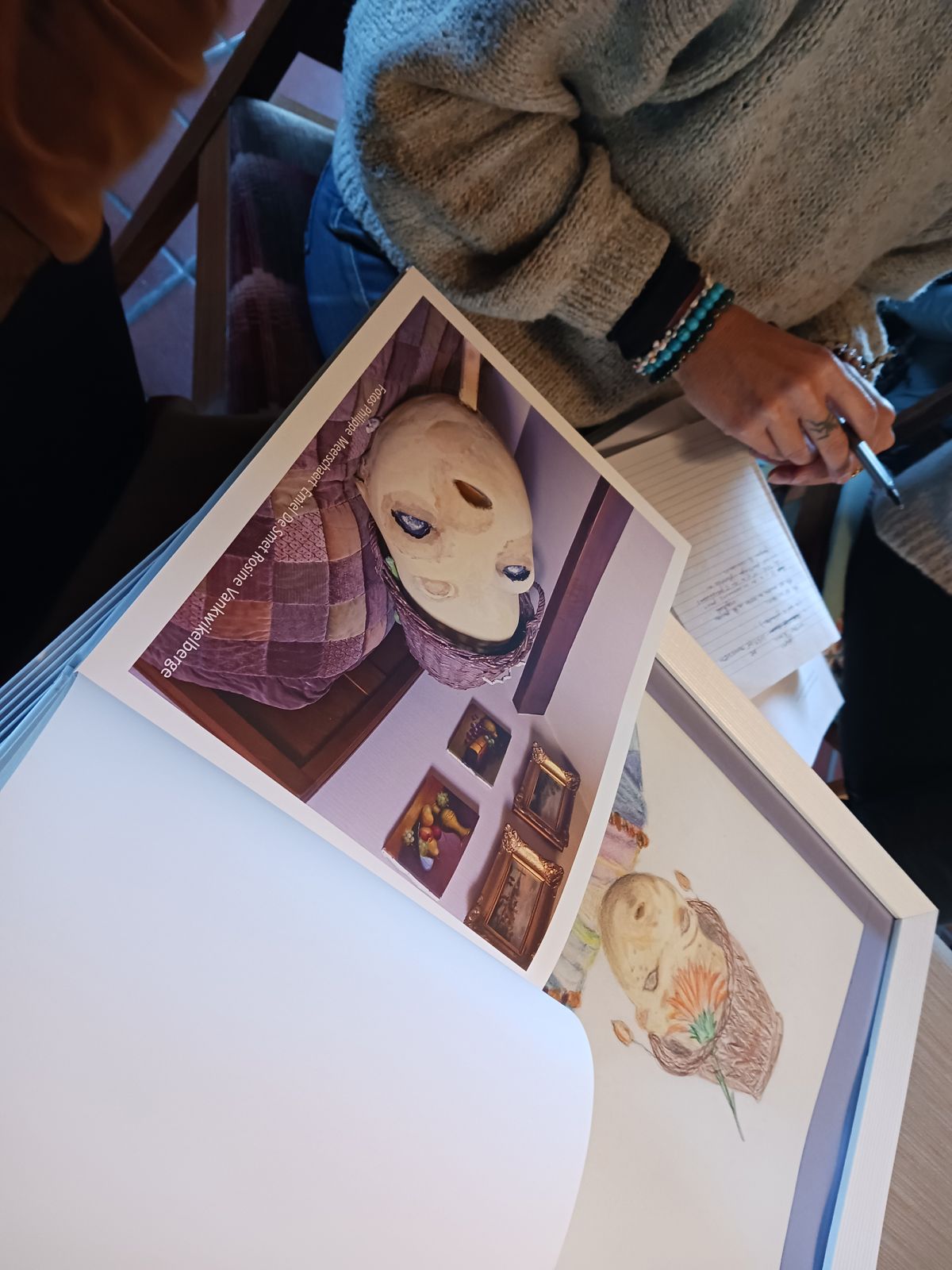

Gorka Arreitunandia Arinas, Arkaitz Arrizabalaga Astigarraga, Alex Baudin, Joseph Bernard, Corine Bogemans, Valérie Boignard, Sébastien Bracq, Julien Coget, Francis De Hertog, Éléonore De Hertog, Emiel De Smet, Joaquim Decoster, Lydwine Frennet, Olivier Gilkain, Mikel Iñarrairaegi Etxano, Karl Libeert, Karin Meskens, José Nuns, Delphine Patiny, Christian Rius, Anne Schumacher, Christophe Simon, Annie Tack, Linda Traets, Corinne Van Israël, Rosine Vankwikelberge, Laetitia Vansnick, Laurence Vits, Philippe Wery

Young Curators Programme (YCP)

Coordination

Laila Melchior

Participants

Giorgia Calamia, Louis Lallier, Thibaud Leplat, Davide Musco, Hugo Roger, Paula Swinnen, Camille Van Meenen, Joséphine Wagnier

Institutional partner

◡ ArBA-EsA, Académie royale des Beaux-Arts

Direction

Daphné de Hemptinne

⌒ CARE (Master pratiques de l’exposition)

Educational manager

Aurélie Gravelat

Legal and financial management

Dana Trama

◡ KASK & Conservatorium | Hogent

⌒ Curatorial Studies postgraduate programme

Direction

Laura Herman

Coordination

Isabel Van Bos

Mediation and inclusion advisor

Marijke van Eeckhaut

YCP with the support of

⌒ Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, Direction des Arts plastiques contemporains

Pascale Viscardy

⌒ Vlaamse Overheid

Stan Van Pelt

⌒ BIJ

Laurence Hermand, Marie‑Sophie Wéry

Young Storytellers

Partner schools

⌒ École supérieure d’art | Dunkerque‑Tourcoing

Direction

Thierry Heynen

⌒ ENSAV La Cambre

Direction

Benoît Hennaut

Participants

Lola Demazeux, Josepha Kinsella, Zoë Lambert‑Bernal, Théotim Leclerc, Guennadi Maes, Anselme Sargeni, Mingwang Wang

Production

Giulia Blasig, Marine Urbain

Engineer

SEA + partners (François Laurent)

❍ Autumn

Interns

Eva Georgy, Jules Playa‑Arruego, Soé Ponsonnaille

Principal partners

Degroof Petercam Private Banking

The Merode

LMNO Bruxelles

Partners

Eeckman

Mobull

Sigma Coatings

The Navigator Company

Vidisquare

visit.brussels

Paolo Boselli (Q3RN_Brussels)

Friends of the Pavilion

Super friends

Frédéric de Goldschmidt

Frederick Gordts

Peter and Nathalie Hrechdakian-Oghlian

Ines en Philippe Kempeneers

Joost en Ann De Vleeschouwer-Pieters

Friends

Artcurial, ETE78, Galila’s P.O.C, KU Leuven Commission for Contemporary Art, Ntgrate, The Art Society

And all those wishing to remain anonymous

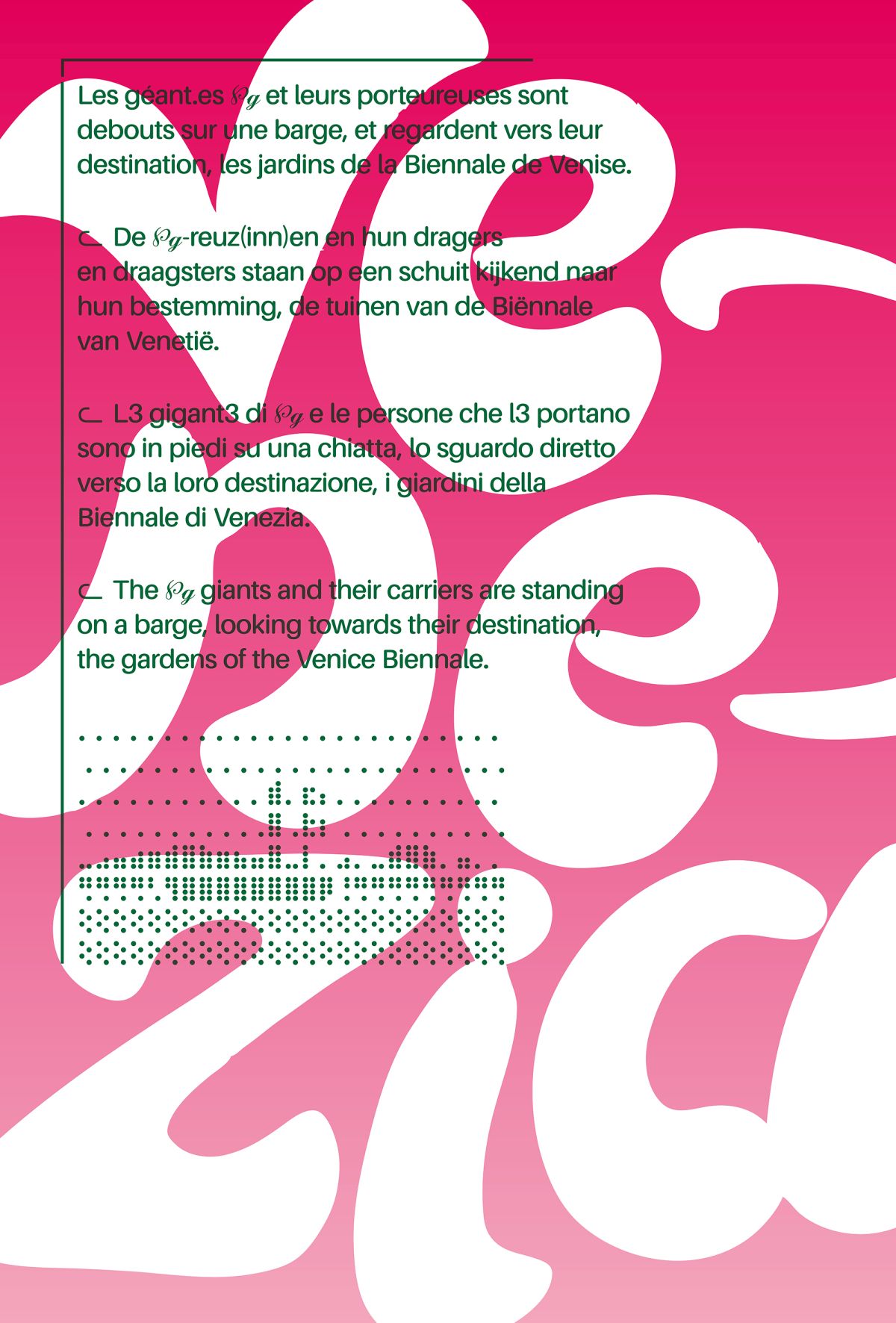

Coordination of translations

Marianne Thys

Translation

Michael Lomax, Federica Romanini, Marianne Thys, Muriel Weiss, Martine Wezembeek

Editing

Françoise Osteaux, Federica Romanini, Marianne Thys, Sheri Walter

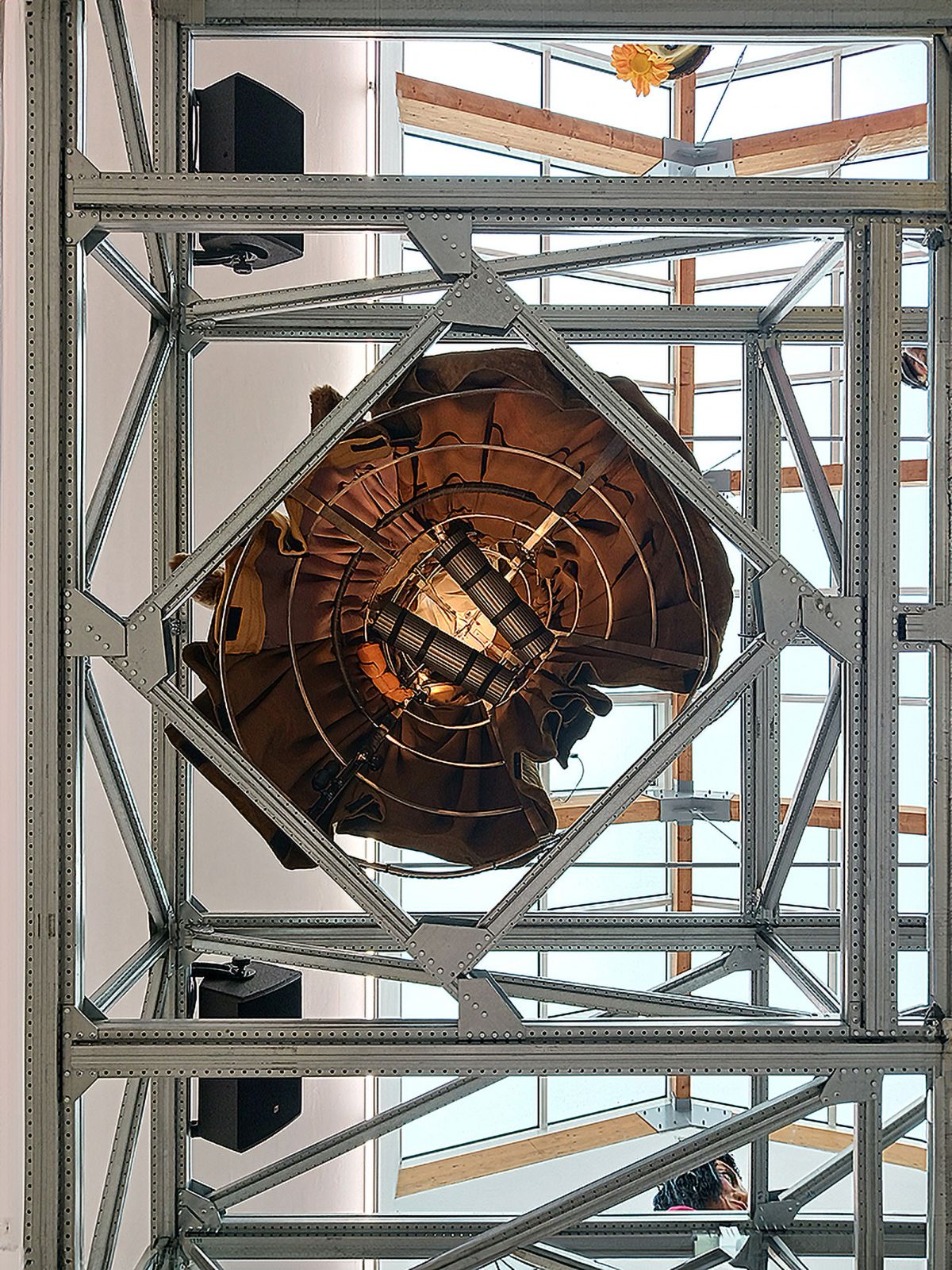

Supplier, architectural structures

Skellet (Jimmy Maes)

Web

variable.club (Nelson Henry, Constant Mathieu)

Guardian of the Pavillion

Giulio Piovesan

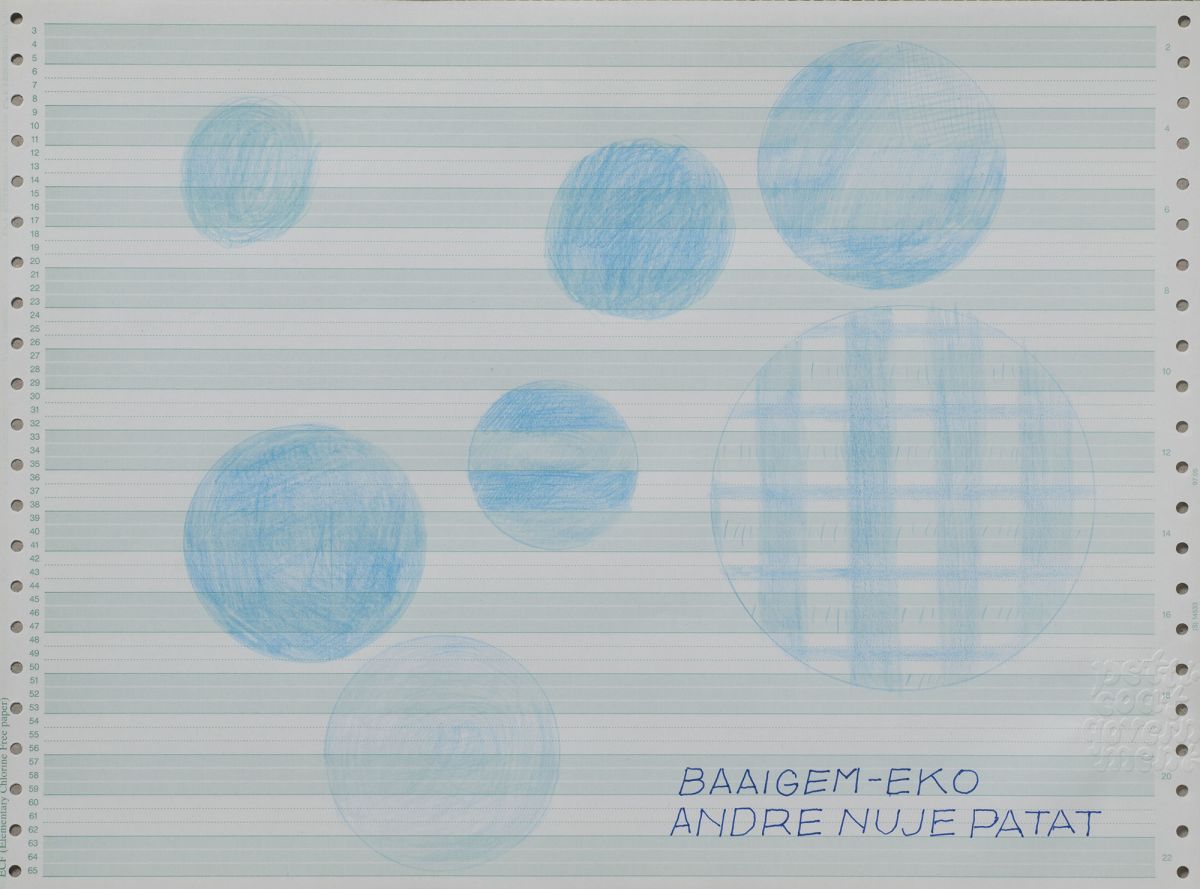

Flag partners

Cas-co Leuven, 019 Gent (Mirthe Demaerel, Koi Persyn, Valentin Goethals)

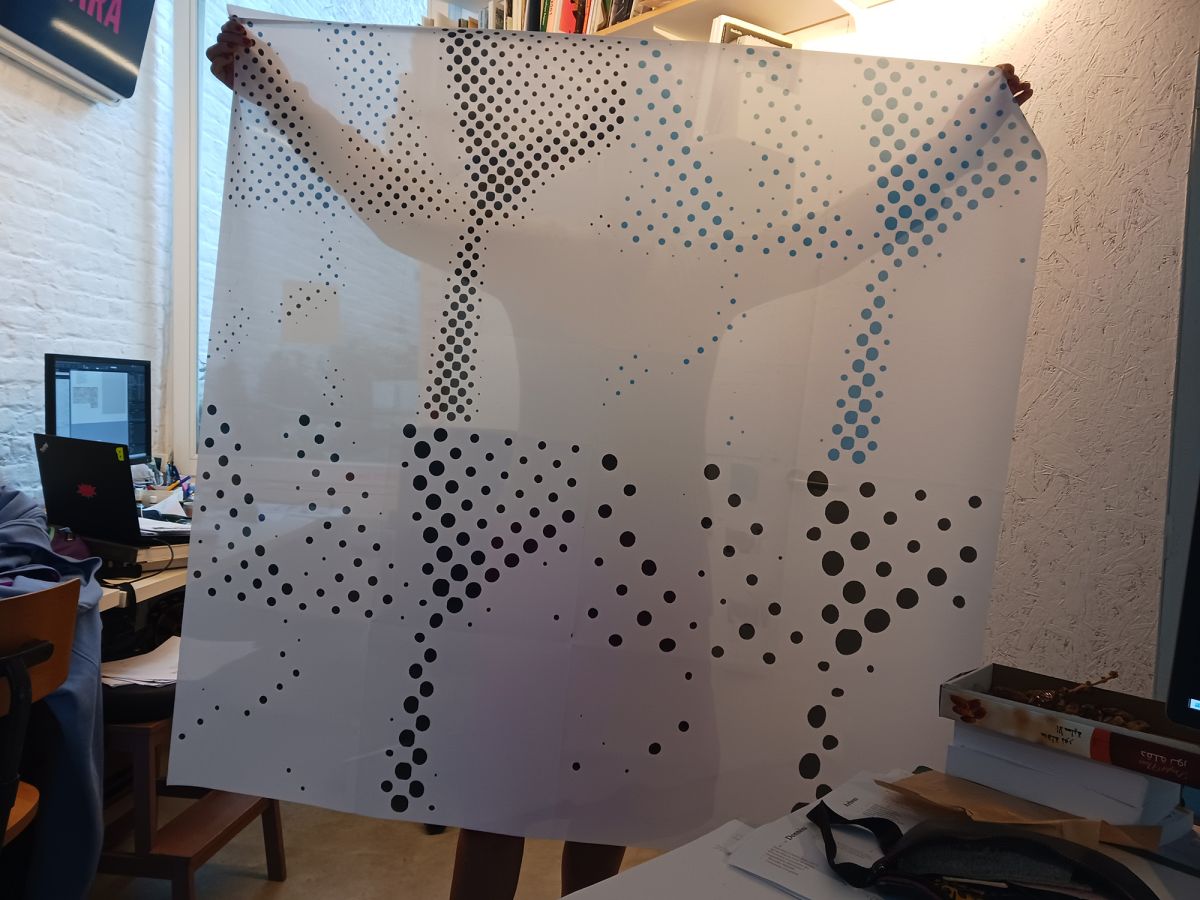

Laser cutting flag-tablecloth-curtain

Atelier CNC (Kenny Vanden Berghe)

Flag-tablecloth-curtain making

Visix

Technique and production (BE)

CMVD (Christoph Van Damme)

❍ Winter

Catalogue, contributions

Maximilien Atangana + eli lebailly, Jean‑Baptiste Carobolante, Manah Depauw, Benoit Dusart, Silvia Mesturini, Young Curators Storytellers, Alexis Zimmer, l’art même (Christine Jamart)

❍ 2024

Audiovisual

Vidisquare (Pascal Willekens, Quinten Verhelst)

Light

Licht (Chris Pype, Luc Van De Walle)

Textile expertise

Flore Fockedey

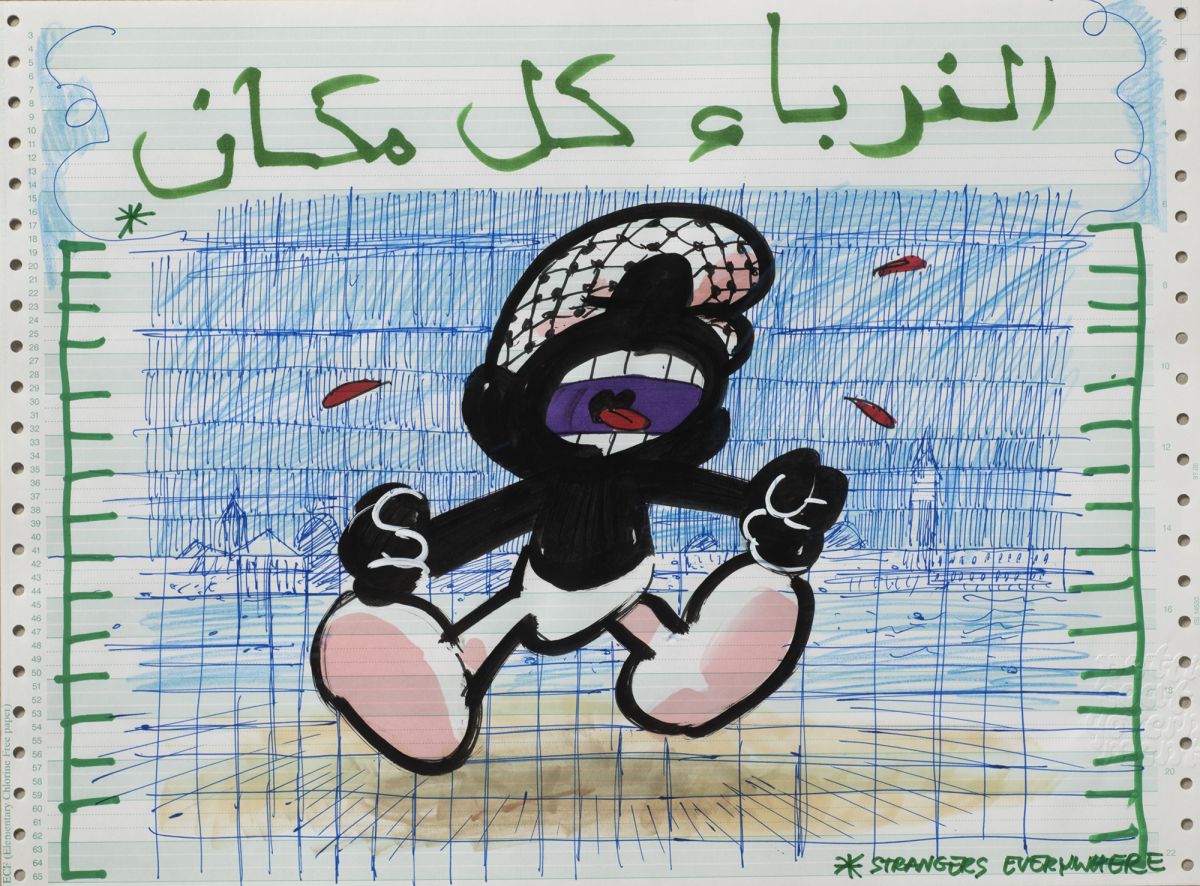

Ceasefire now !

Camera

Charlotte Marchal, Vincent Pinckaers

Sound recordist

Lazslo Umbreit

Photography

Lola Pertsowsky

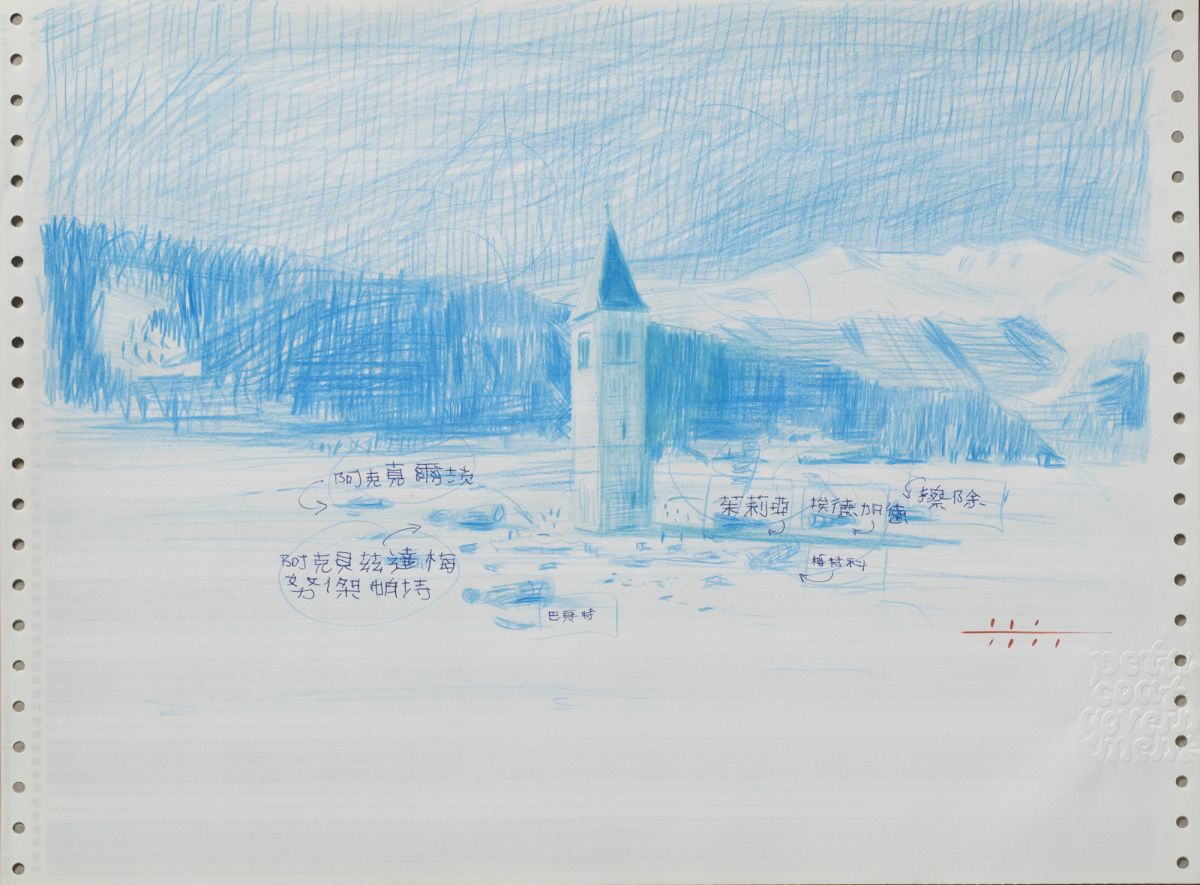

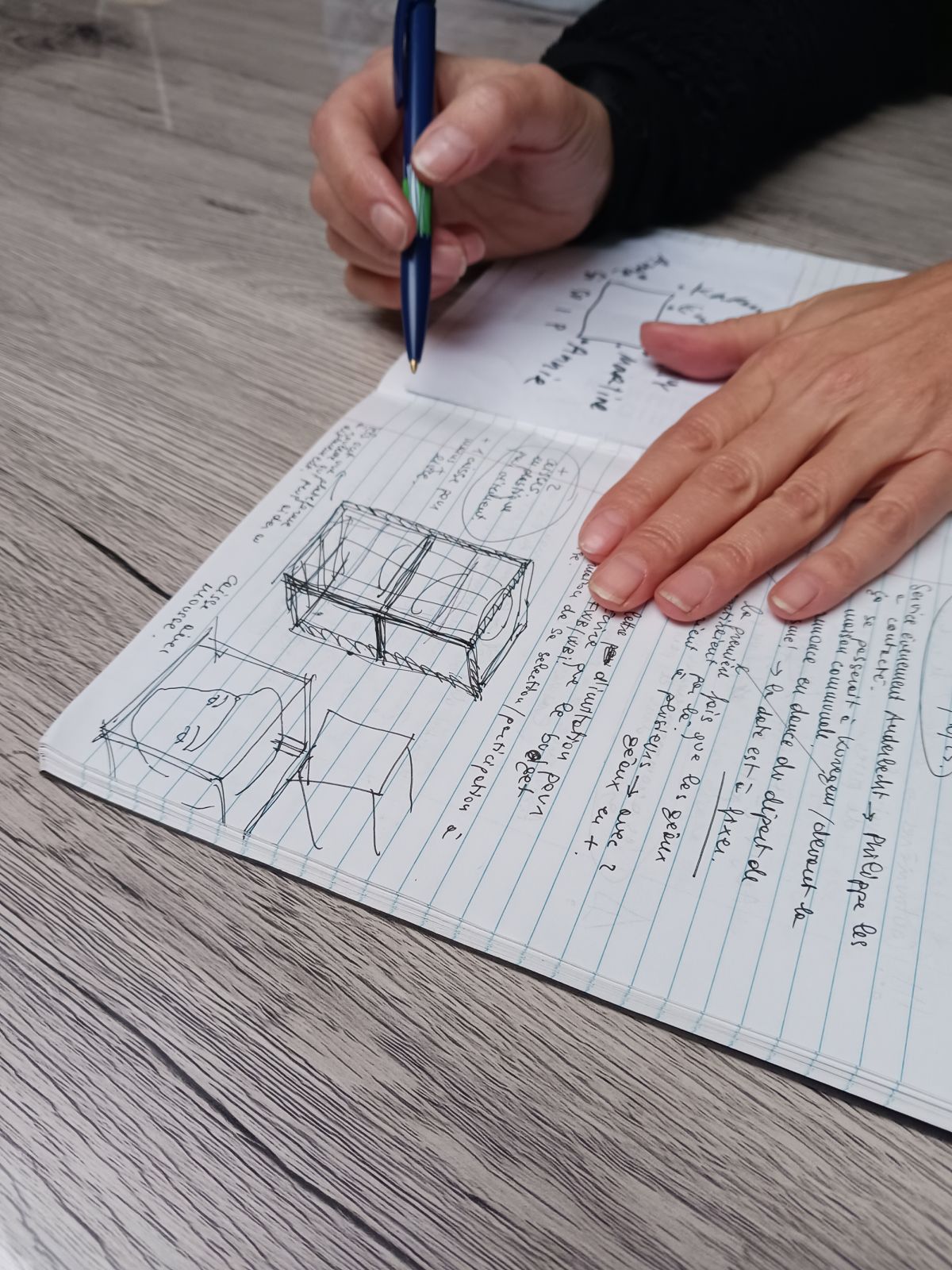

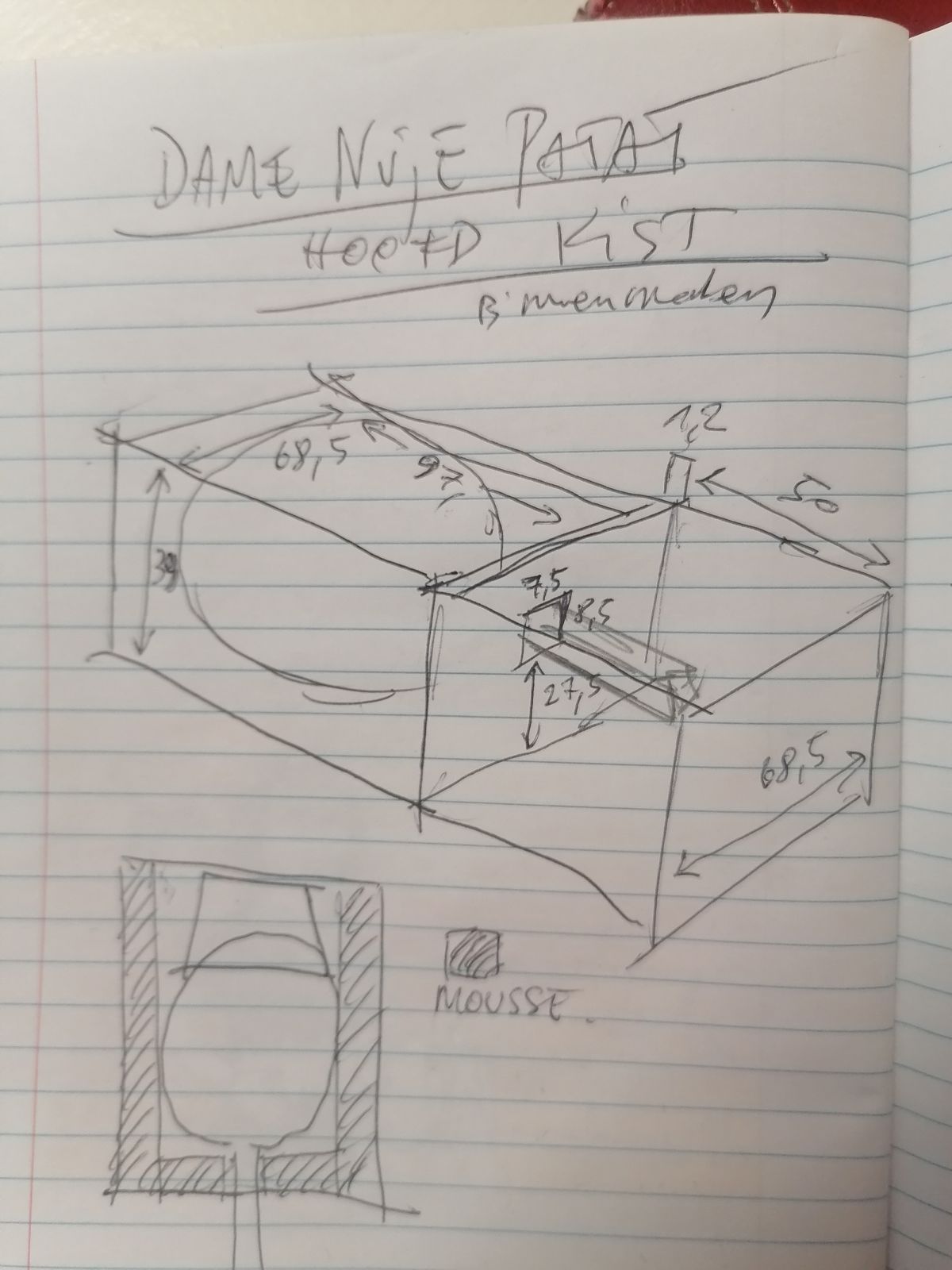

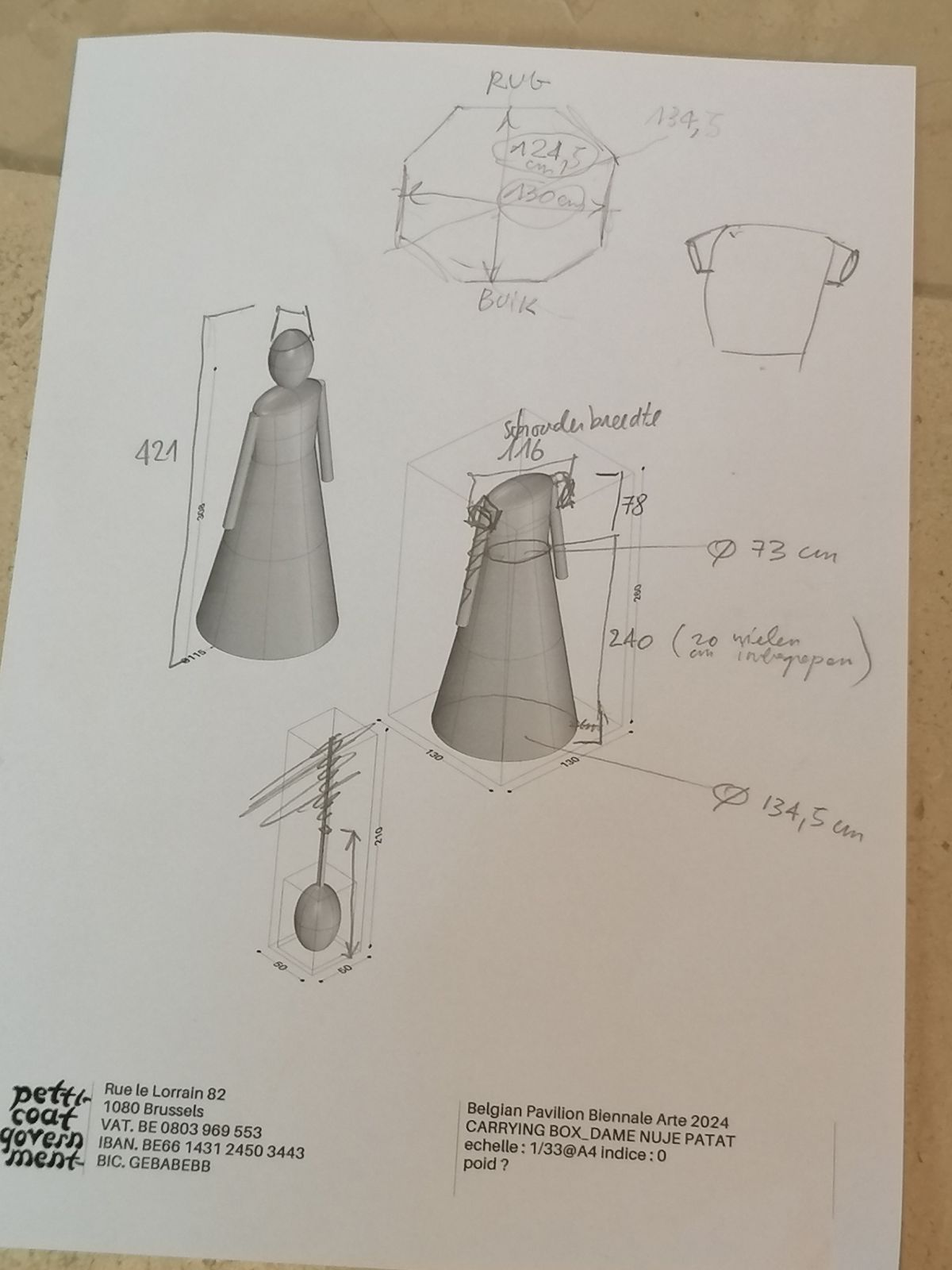

Photographs of the drawings

Philippe Degobert

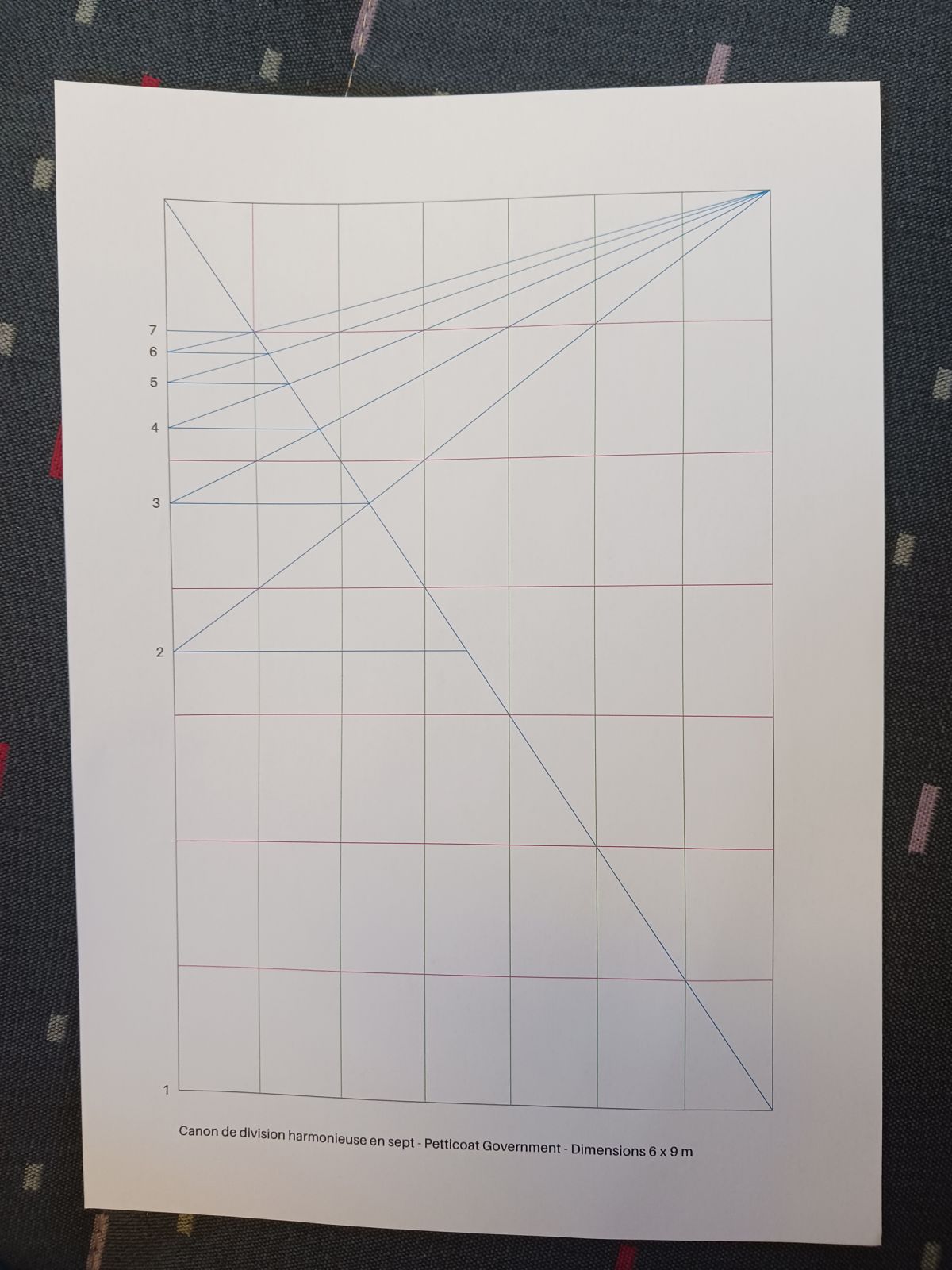

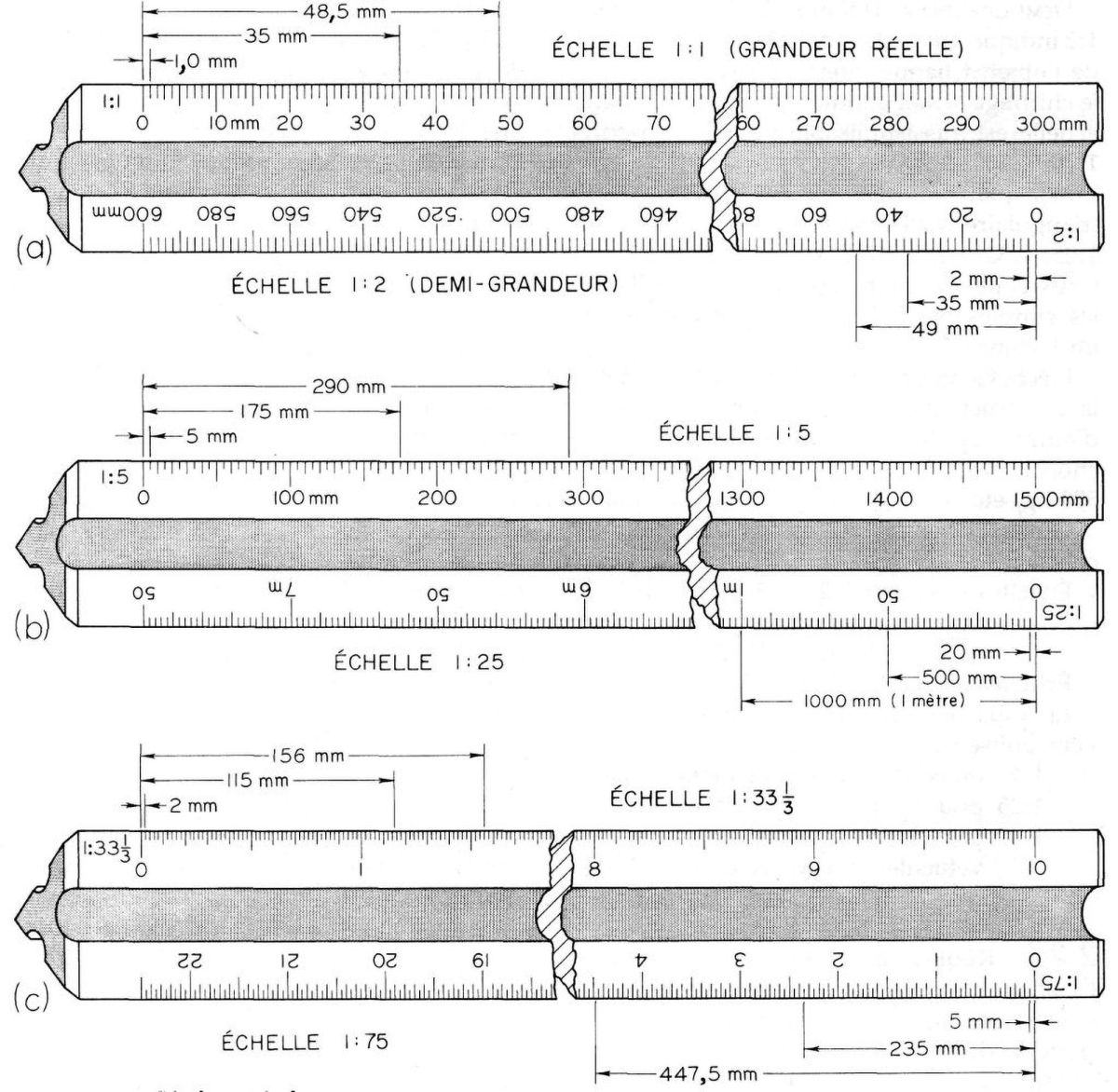

Scale ruler

Cutch Pro (Isabelle Goëtt)

Newspaper printing

RCS (Daniele Povelato, Marco Erriquez, Augusto Musi)

Paper catalogue

The Navigator Company

Telescopic flags

◡ Academie voor Beeld, Muziek en Woord Stad Menen

◡ Projectatelier

Yvan Derwéduwé

Participants

Marina Balloy, Johan Behaegel, Sebastien Delepaut, Vesna Dodic, Katrien Jacques, Veerle Kimpe, Luc Nichelson, Heidi Nolf, Rudi Onraedt, Linda Platteau, Patrick Vandaele, Rita Vandenbroucke, Klaas Verschoore

❍ Spring

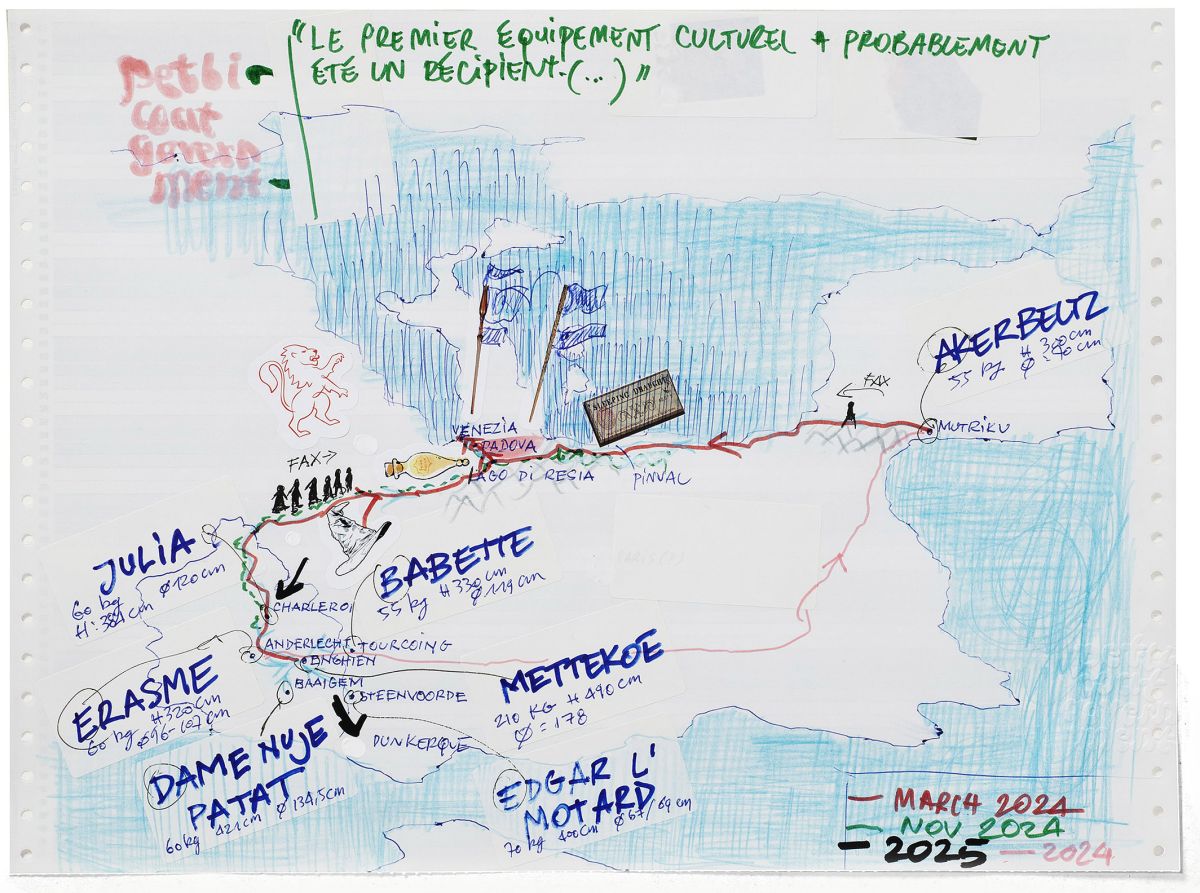

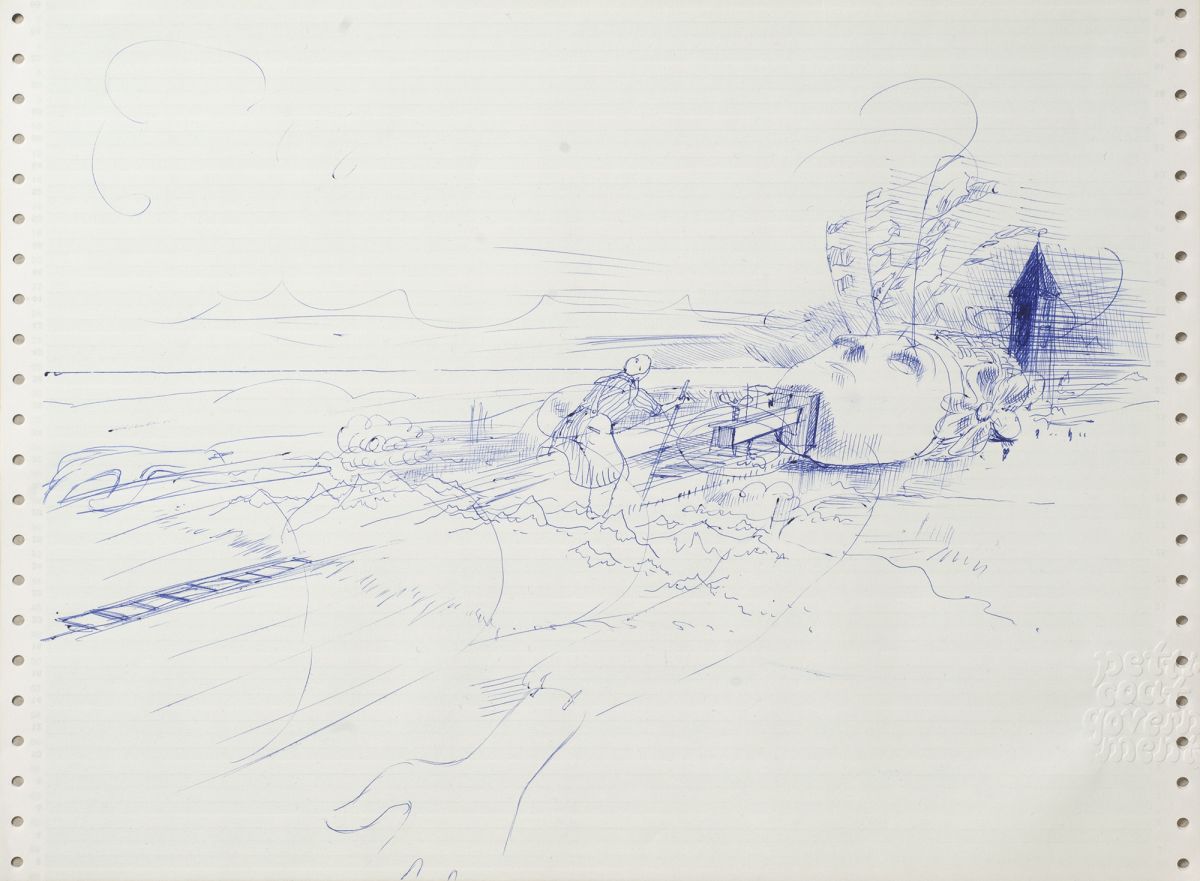

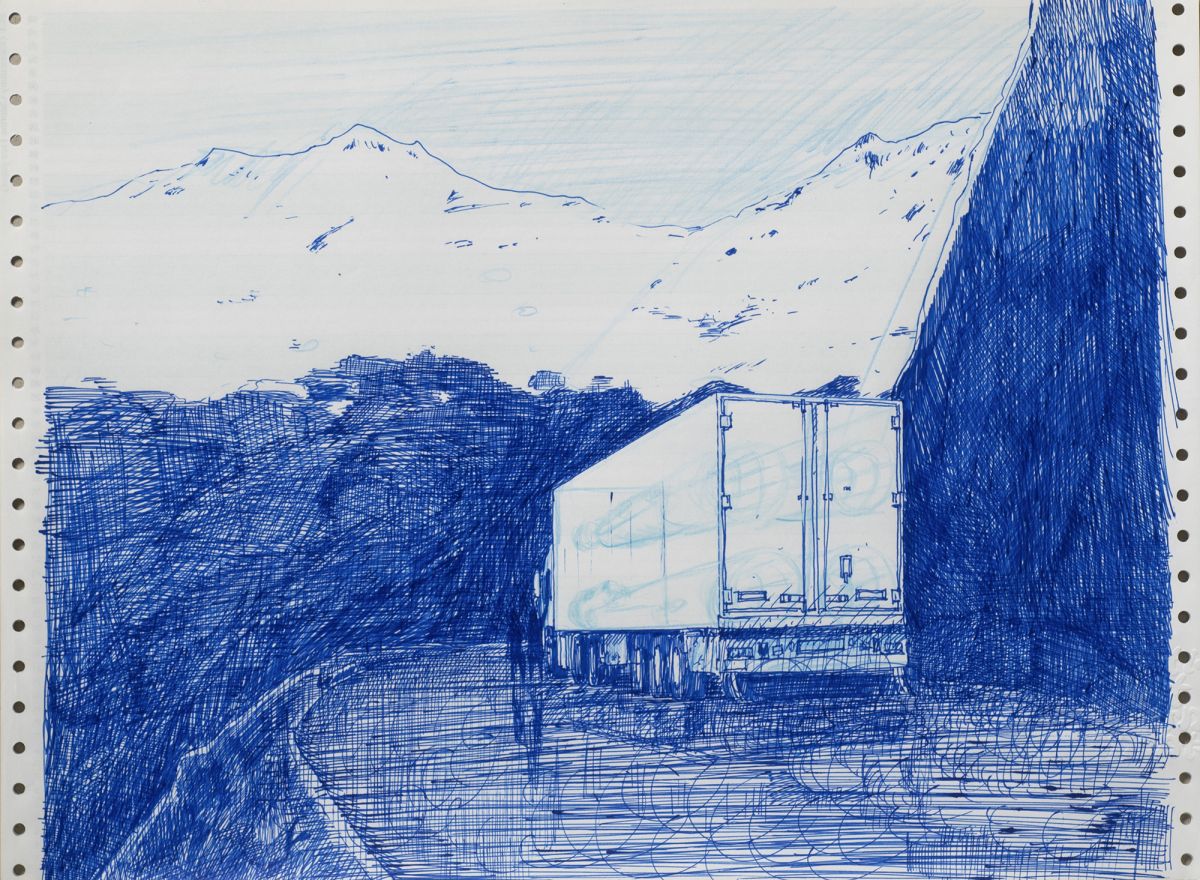

Transport and logistics of giants

Anna Kolodziejczyk + Jacques Lejuste,

Entreprise de Travail Adapté

ETA Enghien (Patrick Godart), Dick Transport (Wim Dick, Jonas Gailly)

Logistics

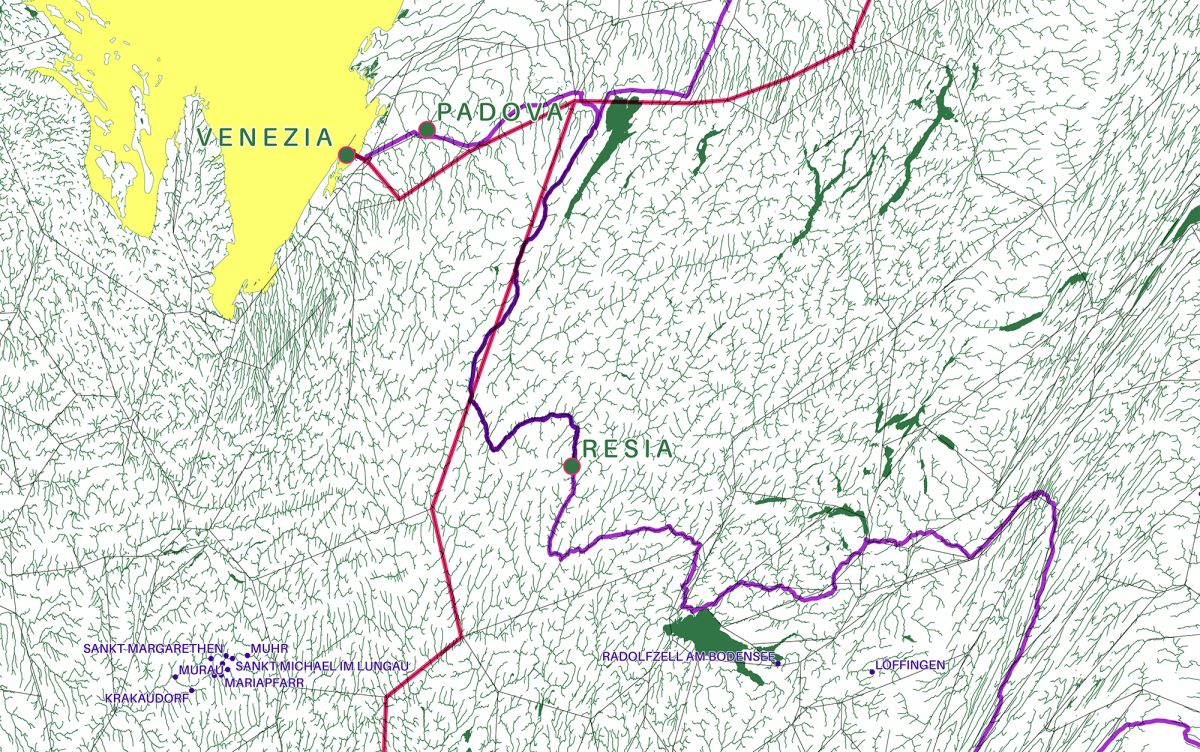

APUS & Les cocottes volantes (Charlotte Lambertini), Voyages Léonard (Sylvie Darcis, Pascal, Cédric, Benoît, Marc), Reschenpass (Gerald Burger), Vinterra (Peter Grassl)

Fanfare Salamba, Molenbeek

ᕃ = Ateliers Claus, Brussels (recording)

ᓇ = Resia

Composition, direction, snare

Moha Ezzatvar ᓇᕃ

Piccolo trom

Wojciech Keblowski ᕃ, Nathalie Méllinger ᓇᕃ, Coline Ozenne ᓇᕃ, Mélanie Spinnoy ᓇ

Tom drum

Ihssan Amzib ᓇᕃ, Benedikte Coussement ᓇᕃ, Simona Denicolai ᓇᕃ, Erika Faccini ᕃ, Soki Kinanga ᕃ, Jan Ockerman ᓇ, Benjamin Tollet ᓇ

Large bass drum

Mustapha Belzaham ᓇᕃ, Babak Rahimi ᓇᕃ, Sébastian Strycharsky ᓇᕃ

Ganzà

Philippe Chatelain ᕃ, Meike De Roest ᓇ, Cécile Huge ᓇ, Sophie Lambert ᓇ, Elisabeth Lebailly ᕃ, Michela Sacchetto ᓇᕃ, Evelyne Scuflaire ᓇ, Peter Veyt ᓇ

Tambourine

Stéphanie Lejeune ᓇ

Recording

Roel Snellebrands

Sound design

Senjan Jansen

Fanfare Filharmonix, Jette

Artistic direction

Peter Veyt

Clarinet

Thierry Becker, Cécile Huge, Sophie Lambert

Transverse flute

Evelyne Scuflaire

Alto saxophone

Meike De Roest, Stéphanie Lejeune

Tenor saxophone

Pieter Vanden Heede

Baritone saxophone

Jan Ockerman

Pan del Doge

Toletta, Venezia

Beans

Cesare Tosi, Murano

Technique and production (IT)

Green Spin

Direction

MA Gaston Ramirez Feltrin, Arch. Dino Verlato, Arch. Michele Zordan

Team

Nicola Beraldo, Francesco Bernabé, Massimo Cogo, Chiara Cortivo, Fiorenzo Gomiero, Sandro Lazzari, Luana Masiero, Matteo Trentin, Tomasso Turchet

Security

Geom. Davide Cassandro

Accompaniment

Giulia Laudenzi, Ousman Seye

Tarot

Philippe Koeune

Mediation totebag

Eva Georgy

Drinks

Brasserie Silly, Enghien

Le Bertole

Festa Dedicata

Michele Perini (presidente Circolo Culturale 3 agosto, Venezia), Édouard Jattiot, Ludi Loiseau, Roberta Miss

❍ 2025

Intern

Adam Baillon

❍ Spring

Fermentation workshop (coordination & assistance)

Murielle Dasnoy, Simona Denicolai

Team Eden, Charleroi

Fabrice Laurent, Carmela Morici, Patrick Timmermans, Gaëtan Bourgy, Thomas Collu, Kevin Gomez, Justine Justine Balducci, Gaelle Pelgrims, Anne-Line Duez, Geoffrey Rousseau

BPS22, Assistance

Nadège Metzeler

Kutch, tablecloth - printing and vynil

Espace Plan, Bulle color

Display - Eden Main Room - printing

aboutmonday

Panelists

Maximilien Atangana, Jean-Baptiste Carobolante, Benoit Dusart, Manah Depauw, Vanessa Desclaux, eli lebailly, Silvia Mesturini, Alexis Zimmer

Moderator

Antoinette Jattiot

Fanfare Salamba, Molenbeek

Composition, direction, snare

Sara Moonen

Snare

Bert Lemmens, Nathalie Mellinger, Melanie Spinnoy

Mid drum

Karina Hadouchi, Jorine Ceulemans, Vangeit Mone, Laura Irene Bardella, Bea Bellavia (+ shake), Hebborn Sarah

Tom drum

Olivier Charlier, Simona Denicolai, Benjamin Tollet

Display - Street posters

Clearchannel

❍ Summer

❍ Autumn

Inflatable kutch

Luca Engels

Lille 3000

Charles Bonduaeux, François Breux, Lou Deiss-Veiniere, Eden Dureuil, Vanessa Duret, Pierre Gochard, Matéo Mullet, Sarah Saïfi

Communities around the giants (travellers) in Lille

Pascal Durieux, Maxime Saswalon

Caméra (additional help)

Marie Merlant

Catering

Affamés Assoiffés

Fanfare Salamba, Molenbeek

Direction, mid

Sara Moonen

Snare

Nathalie Mellinger, Youssef Choua

Shaker et little

Annelies Beuls, Michela Sacchetto

Mid drum

Sarah Baur, Beatrice Bellavia, Jorine Ceulemans, Erika Faccini, Floriana Ficarra, Andrea Garcia, Sarah Lefèvre, Jan Ockerman

Bass drum

Olivier Charlier, Simona Denicolai, Karina Hadouchi, Benjamin Tollet, Constantin Tombroff

Percussions Gnawa Molenbeek

Dris Filali, Khaydin Nabih, Rakhis Abdelaziz, Souhib Nikachi, Hamza El Alloufi

FRAC Grand-Large, Dunkerque

Mathilde Carron, Pomme Harbonnier, Aurélien Knoff, Elodie Staes

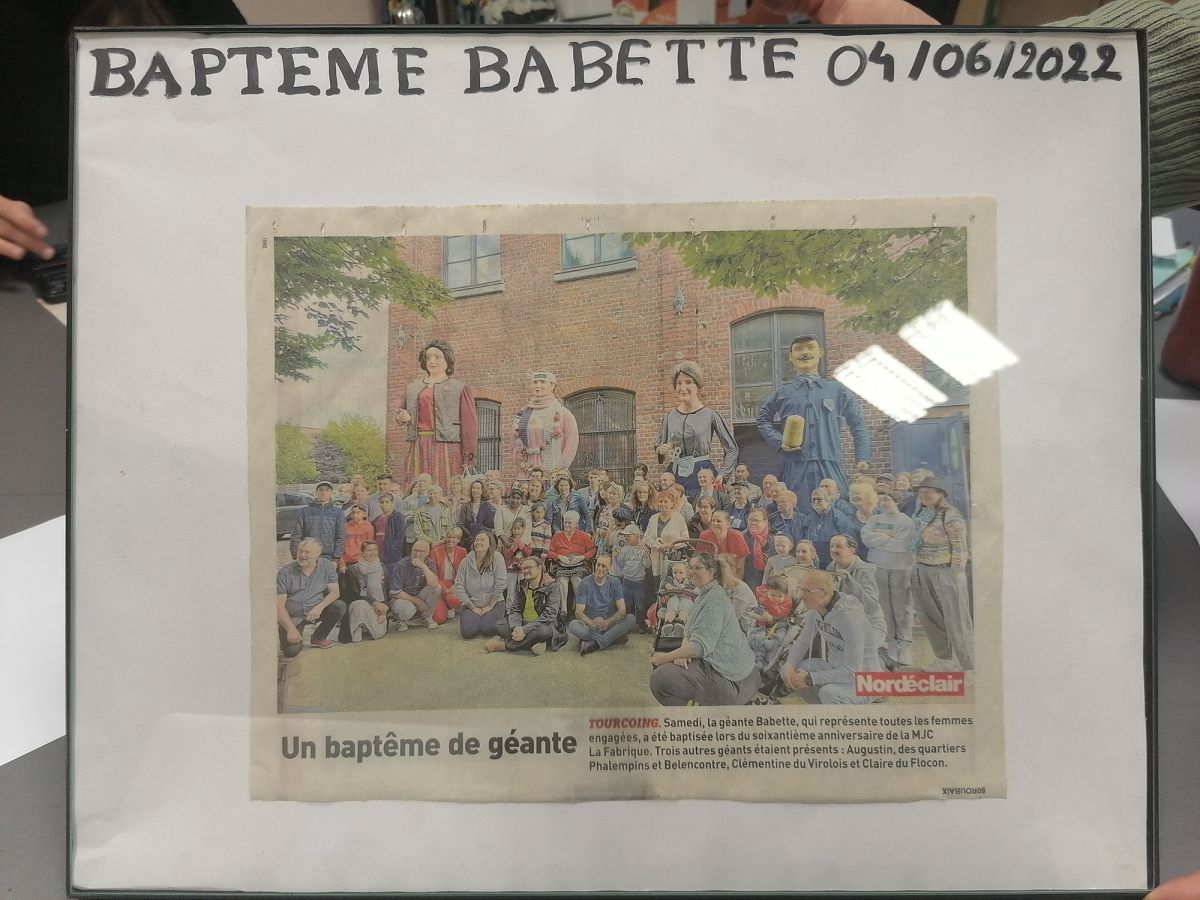

Special thanks

Camille Abele, Bernard Baines, Sophie Baines, Agathe Baumont, Bento (Florian Mahieu, Corentin Dalon, Charles Palliez), Dominique Boiron, Martine Boiron, Céleste Bollaert, Orson Bollaert, Tocia (Marco Bravetti), Aubert Burlet, Café le Petit Lion, Mathieu Collet, Hugo Corbett, Wim De Pauw, Marie Desimpel, Justine Devergnies, Marianne Doyen, Eden Charleroi (Fabrice Laurent, Carmela Morici), André Fockedey, Cristina Galante, Quentin Gérard, Marilyne Grimmer, Julie Guiches, Bertrand Jattiot, Isabelle Jattiot, Félix Lhommel, Jeanne Lhommel, Benoit Lorent, Erwan Maheo, Iris Marano, Luce Marmier, Constant Mathieu, Vincent Mertens, MJC Tourcoing (Marjorie Arthus, Hana Hirti, Laurence Vanhecke), Andrea Montesi, Morion (Federica Bardelle), Annette Neve, Stéphane Olivier, Lorenzo Parretti, Pixie Provoost, Barnabé Provoost, R3B (Giulio Grillo), Antoine Rocca, Marius Rocca, Argentine Rocca, Louise Rocca, Edurne Rubio, Michela Sacchetto, Scalo Fluviale, Anne‑Claire Schmitz, Lepa Stanojevic, Michèle Valette, Luc Van den Eynde, Guilliana Venlet, Judith Wielander